A view of St. Michael’s school as it looked in the early 1960s.

St. Michael

At 5 a.m. of Oct. 9, the sisters at St. Michael’s gathered in the Chapel for Mass. The priest arrived “very much excited and in a fearful state.” He told the sisters that they were in danger if the winds turned directly north. He did not say Mass, but distributed Holy Communion to the sisters and left carrying the Blessed Sacrament.

Shortly thereafter, eight Benedictine sisters and their boarders arrived looking for help and shelter. Their convent had been destroyed earlier that morning. The sisters gave them a cup of tea, but before they could sit down to drink it a messenger arrived to tell them that they were in danger. The Benedictine sisters left and the School Sisters of Notre Dame gathered around the picture of the Mother of Perpetual Help in their chapel and implored her for grace and protection.

An unnamed sister reported in the chronicle that the “wind turned more and more northward and the heavens became brighter and brighter, and the noise and tumult ever greater, and we saw no help in store.” At 8 o’clock that morning the sisters packed all they could, including bedding, clothing and items from the chapel.” Despite being packed, they could not find a wagon to transport them to safety, “since all wagons were already taken and no price however great was sufficient to hire one.”

Finally, two neighbors arrived and transported the sisters to an area 4 miles outside the city and they were then taken to an orphanage run by Poor Handmaids in Rosehill. The writer of the chronicle described the scene: “The streets were filled with people who had been driven from their homes within the past hour, carrying with them what little possessions they could. It was a quiet, subdued people with looks of despair that hurried to the city limits.”

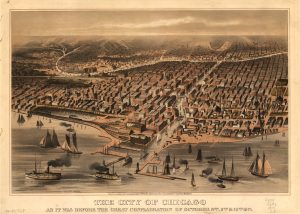

The City of Chicago as it was before the great conflagration of October 8th, 9th, & 10th, 1871. Library of Congress (United States public domain image)

By 1 p.m. all the sisters had left the convent, except for Sisters Emmerentia and Eusebia and a candidate, Theresa Meier, who remained behind to see what could still be saved. The three buried important items, such as their sewing machine, books and groceries, in hopes they could be saved, “but to no avail since our small garden was surrounded by frame structures which were devoured easily by the terrific flames, and our buried belongings went with them.”

A short time later the flames drew near, “the wind ever hotter and the smoke more choking – and the burning pieces of wood flew hither and thither and one’s life was ever in danger.” Sr. Emmerentia went through the convent for one last look. She looked down the street and saw “flames whipping across as tongues of fire from building to building as each was taken in the holocaust.”

Sr. Emmerentia locked the front door of the convent and ran through the garden to the monastery wall. In the alley, the group stood and watched the fire until “the smoke become so dense and the heat so great that we had to flee. The last spark of our hope was gone.”

The next day the majority of the sisters traveled to the Milwaukee motherhouse, but Sisters Emmerentia and Arcadia, along with the priest, drove back to the parish to see what had been destroyed. “This trip back to the parish was risky for everything had been demolished. No sidewalk, no street, no tree, no building stood and the underground was risky due to the debris, and we never knew when the wagon would be overthrown or fall into an abyss.” The convent was destroyed – the only thing that was spared was a candidate’s trunk of clothes, which had been placed near the monastery wall. The sisters searched for their buried items for two hours without luck.

Hope and Determination Prevailed

Everything was destroyed. Everything, that is, except their hope and determination. In March 1872, the chronicle reported that immediately after the fire, “the restoration period began and the more fortunate helped out the less fortunate. Property owners built themselves small huts and the Reverend Fathers [Redemptorist priests who ran St. Michael’s] built cells along the monastery wall and thus arose a new St. Michael. It wasn’t long before a temporary church and school was again erected.” By February 1872, six classrooms were ready and on Feb. 19 the school reopened with 600 children. “Each child wanted to tell his experience and weeks passed by before we were able to really teach. No school materials were available but the children had saved their books and the boys were especially proud to use a half-burned book.”

St. Michael’s School was completely destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire, but it was rebuilt and carried on for many years. The school closed in 1981, with the School Sisters of Notre Dame faithfully serving there for 119 years.

For more information about the Great Chicago Fire, including maps of the burned districts and photographs, see: https://www.greatchicagofire.org/ruined-city/burnt-district/index.html