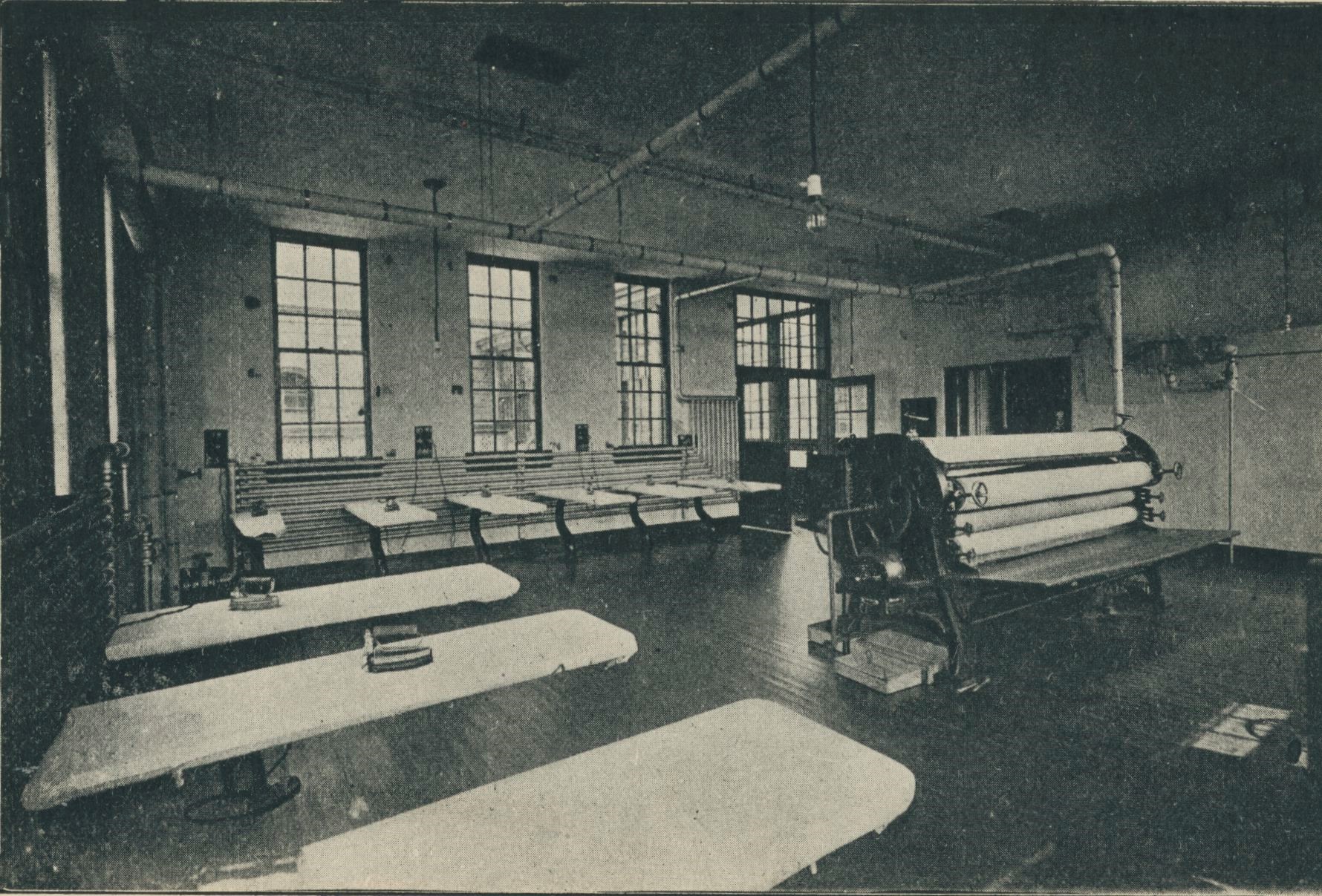

Ripa laundry: The steam laundry at Sancta Maria in Ripa, c. 1910. This is similar to the type of laundry Sr. Zoe would have used.

Sister Zoe Krzysostan

Historians and genealogists often work to recreate peoples’ lives based on information they find in various types of records. This can be difficult, however, when records for a particular person are few and far between.

This is the case for Sister Zoe Krzysostan. Her personnel file provides dates of major events in her life, but it doesn’t give any details about what her life was really like or who she was as a person. Luckily, her obituary helps to fill in these gaps. Sister Zoe died in 1946 and her obituary provides really rich details about her childhood and her work as a laundress after she became a School Sister of Notre Dame. The following is a transcription of her obituary:

SISTER MARY ZOE KRZYSOSTAN

St. Luke, 14, 27.

She was born in Jaraszwo, in German-occupied Poland, October 31, 1859, the sixth of a family of nine children, three of whom died in infancy. When of school age Catherine attended a school taught by a school master in her native land. Because the family decided to emigrate to America she was granted the rare privilege of receiving Holy Communion at the early age of eleven. Soon after this happy day the parents, Thomas and Margaret Krzysostan, nee Diz, with their six children bade farewell to their native land and after a dangerous voyage landed in Baltimore. After leaving the ship the distressed father and mother surrounded by their little children stood near the port not knowing in which direction to walk, neither could any of them speak the language of the country. But, God always cares for His own. A kind Polish gentleman noticed their predicament and forlorn appearance and asked them where they wished to go. They did not know. He advised them to go to Chicago, the city that was being reborn, where they would find groups of their own country-men, and work plentiful. They followed his advice.

When they arrived in Chicago they found it devastated by fire.* No homes were to be had. In their desperate need they sought help from a Polish priest at St. Stanislaus who not only advised them but provided hospitality, permitting them to live in the basement of the church until they could find more comfortable quarters. The father immediately sought and found work with a railroad company. He worked just seven days when he was accidently killed by a train. The grief-stricken mother with her six half-orphaned children hardly knew which way to turn. The basement was cold and damp, and she was told by the sexton that she must leave in three days. Father Vincent Barzynski, the pastor of the parish, provided a tower of strength in those dark days. He saw that the family was settled and procured work for the older children. The mother kept on repeating: ‘God is good. We will all be good and God will care for us.’

When Catherine was fourteen years old she found employment where they manufactured paper bags. When going to work she daily wore the customary head dress, the modern ‘Babushka,’ but in those days a distinctive foreign head gear. Her American companions suggested that upon receipt of her weekly wages on Saturday, she buy a hat for herself. During the week Catherine, on her way home from work, went window shopping. She had her hat picked out and on Saturday evening made the purchase. She was delighted with her choice as it had flowers and birds painting on the side. It had no top, but she thought she could fix that herself.

Sunday morning, proud of her new head gear, Catherine went to Mass. The people on the street gazed at her and laughed. She felt more proud because she thought they too liked her new hat. Suddenly one of her companions spied her from a distance and ran up to her exclaiming, ‘Catherine, why are you wearing that lampshade? You can’t go to church like that!’ Poor Catherine! She ran home and with tears rolling down her cheeks she changed her cherished hat for her common triangular shawl. The lampshade was returned to the store, but the wearing of it caused frequent outbursts of laughter whenever the co-workers were reminded of it.

When Catherine was eighteen years old, Father Vincent told her he thought she had a vocation to the religious life. She at that time was enjoying life and did not care about locking herself behind convent walls. Almost suddenly, however, Father Vincent’s suggestion took root in her heart. Now her mental attitude was completely changed. She told him his prayers had been heard, for she had only one desire – to live for God alone under the protection of the Blessed Virgin.

WI, Prairie du Chien: A photo of St. Mary’s Academy in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin where Sr. Zoe worked for 34 years in the laundry.

She entered at St. Stanislaus, Chicago, in 1876 and on August 15, 1877, the portals of the Candidature in Milwaukee were opened for her. After six months she was sent to Elm Grove where she proved a willing worker. July 7, 1880, was her reception day and Novice Mary Zoe’s happiness was unbounded. For six years she labored in the Motherhouse laundry in which was then St. Mary’s Institute [a girls boarding school]. When that was given up she transferred to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, to continue her work as a laundress at St. Mary’s Academy where for thirty-five years she spent her energy in washing and ironing for over one hundred boarders and about thirty Sisters. No modern machines, no push button contrivances for machines to start. Her hands and the old fashioned washboard and good soap did the trick.

In 1921 Sister Mary Zoe was sent to St. Stephen’s, Milwaukee, where she worked for God for thirteen years. Then she was again transferred to St. Mary’s, Prairie du Chien, to help in the refectory. Here her eyes faded and her limbs became swollen so in 1939 she was sent to Elm Grove. Even though tired and almost worn out, good Sister M. Zoe would go to the laundry every Monday as long as she was able to walk in order to help fold wash. She just could not be idle.

Sister M. Zoe loved to pray. Her greatest joy was to listen to sermons and to spiritual readings. She cherished a great devotion to the Sacred Heart and the Blessed Sacrament and when her eyesight was completely gone she could be seen groping her way around the chapel making the Ways of the Cross. Frequently she carried an old alarm clock with her to the chapel and when asked why she carried the clock since she could not see the time, she said very naively: ‘There are always good sisters Sister who can tell me the time when I want to know it.’ She was very punctual and did not want to be late for conventual exercises.

The year of her diamond jubilee 1942, Sister became very ill and was anointed July 18. She rallied, however, and in January, 1944, another spell brought her to the brink of the grave and she was anointed a second time. Again she revived and was up and around until the fall of 1946. October 7 she was anointed a third time and it was evident that her Divine Spouse was ready to call, which He did October 19, at 3:30 p.m. while Sister Superior, the nurses, and many Sisters as could get into the room were praying for her. She was buried October 22, 1946.

Several nieces and nephews from Chicago and Milwaukee attended her funeral. May Sister M. Zoe continue to pray for the necessities of the Order and may her prayers for good house candidates bring many good housekeepers to our Candidature.”

* According to records in the Archives, the family landed in Baltimore in May 1871. The Chicago fire occurred in October 1871, so the family must have lived in Baltimore for a period before they went to Chicago.