By Michele Levandoski, Archivist, School Sisters of Notre Dame North American Archives

Today, the School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) are known for their work with social justice issues, but that was not the case in the mid-1960s when Sister Marie LeClerc Laux became involved in the Milwaukee civil rights movement. Sister Marie LeClerc’s social awakening happened as a result of work with the African American community on the city’s near north side. She was also influenced by the writings of Pope John XXIII and the changes within the Catholic Church that were the result of Vatican II.

Three oral history interviews (recorded in 1982, 2008 and 2019), archival materials, newspaper accounts and Sister Marie LeClerc’s personal archives describe her transformation from a young professed sister from a small town to a “radical” who participated in various ways in the Milwaukee civil rights movement.

Author’s note: The civil rights movement in Milwaukee is a very complicated story. The purpose of this article is to tell the story of Sister Marie LeClerc Laux and her participation in these events. To learn more about the people, events and organizations involved, please see Patrick D. Jones’ The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee and the “March on Milwaukee,” a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries and the Wisconsin Historical Society: https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/.

“We had taken a public stand”

On August 28, 1967, Father James Groppi, a Catholic priest in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, and members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Youth Council, along with supporters, marched down Milwaukee’s 16th Street Viaduct toward Kosciuszko Park in support of open housing legislation. Included in that group was Sister Marie LeClerc Laux, SSND.

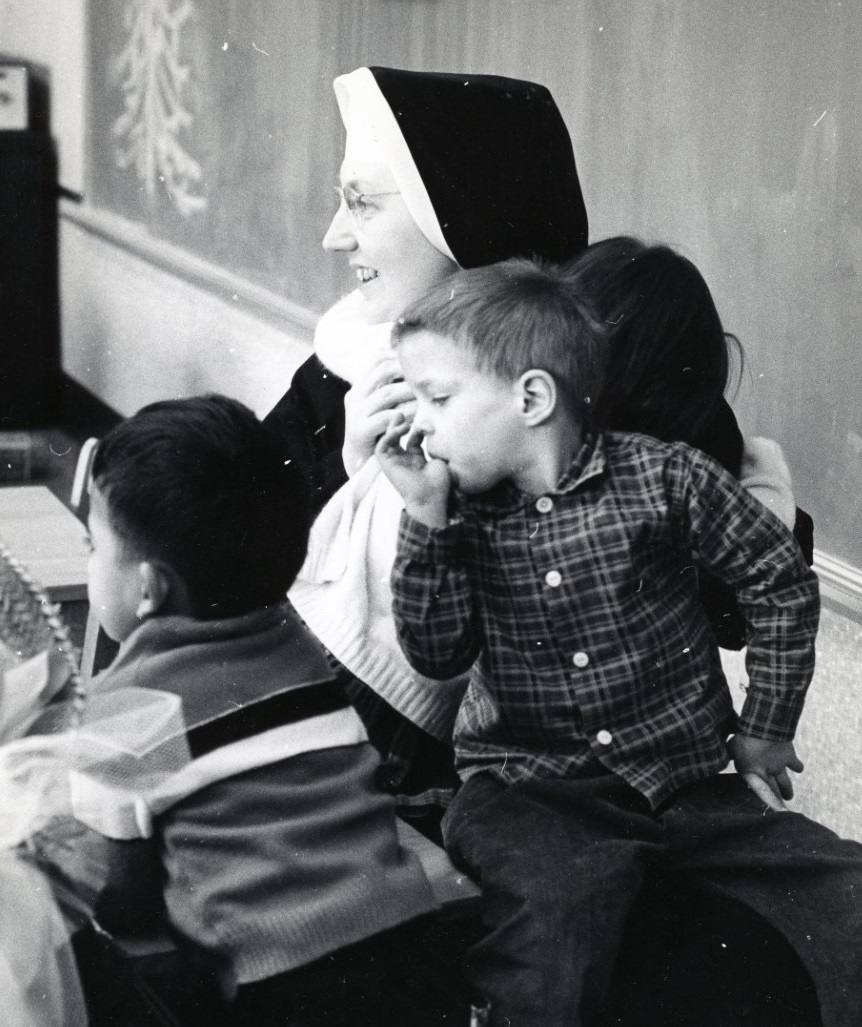

Sister Marie Leclerc Laux, SSND

Sister Marie LeClerc is now 93 years old, but she clearly remembers that march. The police had been alerted and had surrounded the marchers as they crossed the bridge to the city’s south side. Once over the bridge, the marchers were greeted by members of the white community who lined the road, yelling obscenities, throwing things and telling them to go back to the north side where they belonged. As Sister Marie LeClerc and other sisters walked down the street, they passed a former parishioner, who spit at them. “I was shaken by the hatred that we had experienced, but also with a certain sense of satisfaction that we had taken a public stand against [this] type of segregation policy,” Sister recalled.

Reflecting back on her participation in the open housing marches, Sister Marie LeClerc said that many white people in the community couldn’t understand why the sisters were getting involved in “black issues.” She explained why: “Because of course they didn’t want us on the south side and it looked like we were just arousing passions, making people mad, looking for press coverage and as some people said, ‘being Communist dupes.’ But we knew that in order to be part of the black community we had to be part of the black concern.”

“Change our whole way of life”

Glory Mae Laux was born in 1926 in Menasha, Wisconsin. She had been taught by the School Sisters of Notre Dame and thought she would be a good teacher, so it seemed natural to her that she join the congregation. She entered the candidature in 1944 and professed her first vows in 1947, when she was given the name Marie LeClerc.

Sister Marie LeClerc’s first assignment was St. Boniface School in Milwaukee, which was thriving with more than 800 students at the time. Her first year she taught 61 second graders. She said she “almost died” because she could hardly see the end to the line of children she was expected to teach. She later taught fifth through ninth grades. In 1960, she was appointed as the principal and convent superior while still continuing to teach.

Sister Marie LeClerc found it difficult to balance all her responsibilities and give everyone what they needed. Her work was further complicated when the number of children enrolled at the school significantly declined as the neighborhood underwent a radical demographic shift.

Milwaukee was a manufacturing city that attracted large numbers of immigrants. By the early 20th century, the city was ethnically diverse, but almost exclusively white. In 1910, there were less than 1,000 African Americans living in the city. That changed during the Great Migration (1916-1970) when approximately six million African Americans migrated from the South to cities in the Northeast, Midwest and West. In 1945, less than two percent of Milwaukee’s population was African American, but by 1970, that number grew to nearly 15 percent.

African Americans who migrated to Milwaukee lived almost exclusively in the city’s near north side in an area that became known as the “inner core.” In 1940, the inner core consisted of approximately 75 city blocks, but with an increasing number of African Americans moving into the city, the boundaries of the inner core pushed north and west. The neighborhoods that bordered the inner core changed rapidly as whites moved to the suburbs. By 1960, the inner core was six times larger than it had been in 1950.

St. Boniface School was located in the heart of the inner core, so Sister Marie LeClerc witnessed these changes in real time. Since African Americans were blocked by various means from living in other parts of the city, they often had little choice but to move into inner core neighborhoods. The rapid rise in the number of African Americans moving into the inner core stressed an already tight housing market. Houses in these neighborhoods were overcrowded and in poor condition. Unemployment and underemployment led to poverty and a rising crime rate. The lack of resources needed for improvement caused entire neighborhoods to decay.

A challenge for Catholic churches in the inner core was that the African American community did not have a strong history with the Catholic Church and many of the neighborhood’s residents didn’t trust the priests and sisters. Sister Marie LeClerc experienced this suspicion firsthand one day as she walked down the street with another sister, both of them wearing their black habits. As they passed one house, an African American mother ran out of the house and grabbed her children, saying, “Get away from those black witches!”

Despite these fears, many African American parents sent their children to St. Boniface School because they heard the SSND were good teachers and they wanted to give their children access to the best education they could. However, the children who came from the South had attended schools with lacking resources and many were not able to meet the standards outlined by the Archdiocese of Milwaukee’s education department.

Sister Marie LeClerc and the other sisters at St. Boniface faced an uphill battle. The number of students at the school had declined sharply; those who did attend struggled to pay the tuition and many were behind academically. Despite these obstacles, the sisters saw an opportunity. “We knew that we were being drawn into a moment of history that was going to be very important for the people in our neighborhood,” said Sister Marie LeClerc. The sisters decided that they were going to go all out and that no sacrifice was too great.

The sisters at St. Boniface understood that if their students were going to be successful, the teachers needed to make some changes. “And as these years kept going on, we knew we were going to have to change our way of teaching, change our attitudes, change the way we understood, change our whole way of life as a matter of fact,” Sister Marie LeClerc reflected. The sisters wanted to help the children, but first they had to help themselves learn how to best serve the students.

The sisters at St. Boniface understood that if their students were going to be successful, the teachers needed to make some changes. “And as these years kept going on, we knew we were going to have to change our way of teaching, change our attitudes, change the way we understood, change our whole way of life as a matter of fact,” Sister Marie LeClerc reflected. The sisters wanted to help the children, but first they had to help themselves learn how to best serve the students.

Sister Marie LeClerc and her teachers employed a variety of methods to assist their students. First, they reverted back to a very basic education and eliminated all the “frills.” According to Sister Marie LeClerc, the students had “phonics coming out of their ears” and were drilled on basic math. She also recruited students from Marquette University and local Catholic high schools to tutor the children after school. She applied for federal programs that would help the school receive needed materials. For example, in 1965, the schools’ reading center, language development program, guidance program and Head Start, were all funded by federal grants.

Sister Marie LeClerc and other principals at inner core Catholic schools created a committee to propose that the Archdiocesan education department relax some of their rules and testing standards for students in the inner core. There was a lot of back and forth that eventually resulted in some flexibility. In September 1965, the sisters at St. Francis School (also located in the inner core) reported in the school chronicle that the Archdiocesan superintendent of schools “released the inner core schools from the diocesan curriculum, that is from the adherence to diocesan regulated texts and tests. Each teacher may now teach and use materials suited to the individual needs of the children.” This allowed the teachers to use books that better reflected the lives of their students.

The sisters also understood that they needed to incorporate a sense of cultural identity into the curriculum, so they started emphasizing black contributions to American society. For example, in February 1965, the school celebrated Negro History Week, in part, by watching filmstrips about George Washington Carver and Mary McLeod Bethune.

Sister Marie LeClerc and the teachers at St. Boniface also tried to provide experiences to broaden their students’ lives. In 1965, the school enacted a policy that one class would take a field trip each month to visit museums, parks and fairs, etc. In November 1965, the third grade visited a pumpkin farm while the fourth grade visited Graf’s Soda Pop Factory.

Despite these efforts, the number of children at the school continued to decline and the school struggled to stay afloat financially. At the same time, the staff at St. Boniface was being dragged into political issues that had nothing to do with Catholic schools, such as the segregation of Milwaukee’s public schools.

“Education will transform people”

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state laws allowing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional and American schools were ordered to integrate. The Milwaukee School Board created an integration plan called “intact bussing.” Under this policy, entire classes of students from overcrowded, inner core schools would be bussed to a school that had room to accommodate them.

On school days, students and their teachers would report to their school and would be bussed to the receiving school where they would remain together as a class, instead of being incorporated into existing classrooms. In many instances, the bussed students would have a separate recess or would be bussed back to their original school for lunch. At the end of the day, the bussed students would return to their original schools to be dismissed. From 1958 to 1972, more than 36,000 students were bussed using this policy, the overwhelming majority being African American.

In 1964, the newly formed Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC) began a series of direct-action protests against school segregation and intact bussing. In 1964, MUSIC sponsored a one-day boycott of Milwaukee Public Schools to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Brown vs. the Board of Education decision. Freedom Schools, which emphasized African American history and activism, were created as an alternative to the children who participated in the boycott. In September 1965, MUSIC decided to sponsor a second school boycott, which was scheduled for October 18.

The priests and sisters working at inner core parishes and schools gathered to discuss the boycott. The group decided that if they were going to identify with the black community, they had to support the boycott. On September 28, 1965, 24 priests released a statement that read, in part:

“We believe that segregated education is inherently unequal…Whether segregation is the result of state policy or merely reflective of neighborhood condition, makes little difference to its victims…As Pope John XXIII stated in his encyclical Peace on Earth, ‘He who possesses certain rights has likewise the duty to claim these rights as the mark of his dignity…’ Now it is necessary for parents to boycott the schools. We support them because they must claim their rights as a mark of their dignity.”

At the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s, the Catholic Church avoided controversial racial issues. Although priests and sisters working in the inner core created social programs for African Americans, they did not actively challenge racial discrimination. However, in the 1960s, reform movements within the Church began during the Second Vatican Council. Some of the most important changes to come out of Vatican II were the call for the Church to become more involved in modern life and the reaffirmation of the Christian duty to help the poor and downtrodden.

Sister Marie’s LeClerc’s beliefs about social activism were strongly influenced by both the charism of the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the changes brought by Vatican II. When asked why she cared about what was happening in the public schools, she responded that it was about education. The SSND mission is to “transform the world through education,” and the congregation emphasizes educating the whole person. As an SSND, she understood the power of education and was committed to seeing that each child, regardless of religion or race, had access to a good education. “Education will transform people. And [the] right education will transform them into loving, responsible people,” she explained.

Equally influenced by the changes of Vatican II, Sr. Marie LeClerc speaks passionately in her oral history interviews about the “beautiful documents” written by the Vatican Council that called for Catholics to be responsible for each other and stated that each person’s dignity needs to be honored. “The whole movement of the Church at that time taught me about social justice,” she said. The priests at St. Boniface supported her in this.

Equally influenced by the changes of Vatican II, Sr. Marie LeClerc speaks passionately in her oral history interviews about the “beautiful documents” written by the Vatican Council that called for Catholics to be responsible for each other and stated that each person’s dignity needs to be honored. “The whole movement of the Church at that time taught me about social justice,” she said. The priests at St. Boniface supported her in this.

The pastor at St. Boniface Catholic Church, Father Eugene Bleidorn, was already active in the Cardijn movement, which emphasized observing and judging a situation in light of the Gospel and then acting. Sister Marie LeClerc described Father Bleidorn as an intellectual who understood the Church’s teachings during this period. She attended his small group discussions on the ramifications of the Vatican II documents.

Father James Groppi, the assistant pastor at St. Boniface, had been influenced by his work in the South, including participation in the marches from Selma to Montgomery. He was inspired to engage in nonviolent direct-action, such as marches, sit-ins and boycotts, and became a well-known figure within Milwaukee’s civil rights movement of the 1960s.

During this period, priests and sisters working in the inner core, who could see the effects of segregation firsthand, believed that Vatican II documents gave them the approval of the Church authorities for their activities. The priests and sisters at St. Boniface were at the center of this new thought and social action, because they felt emboldened to act according to their conscience.

On October 7, 1965, five of the inner core parishes released a statement, written by Sister Marie LeClerc, describing their position.

“To give a child an inferior education through segregated schools and intact bussing, makes him unfit to compete successfully in the labor market, thus forcing him to low income, poor housing, congestion and the countless miseries of unrelieved poverty. This is perpetuating base injustice…As Christians we must protest against making children the victims of adult inaction and apathy…We deplore having to use the means of a public school boycott to force the school board and the people of the city of Milwaukee to look at the children whose rights to be treated as human beings are daily being denied…Therefore, on October 18 and the days following, St. Benedict, St. Boniface, St. Elizabeth, St. Gall, and St. Francis Schools will open all available facilities. Freedom Schools will be held on our premises. Some of the sisters, priests and lay teachers of our schools will teach in the Freedom Schools throughout the area…” (Note: St. Boniface, St. Elizabeth, St. Francis and St. Michael were staffed by SSND; St. Gall and St. Benedict were staffed by Dominican sisters.)

The statement makes clear that all five parishes intended to actively participate in the boycott, but behind the scenes there were varying levels of commitment. Sister Marie LeClerc said that each priest and sister had a different idea of what supporting the boycott meant to them personally. The sisters at St. Francis School and St. Elizabeth School were divided – some believed in the boycott in principal, but not in action. Others disagreed, even with hostility, believing that the boycott was just part of Father Groppi’s desire for attention. The staff at St. Michael School did not join the boycott at all. The group at St. Boniface had the support of the parishioners, and because of Father Groppi’s activism, they took the most radical stance, which was to actively participate in the boycott by acting as a Freedom School. One of the sisters at St. Francis School wrote about these events in the convent chronicle: “St. Boniface is taking a very loud and dramatic point of view.”

A week later, each pastor received a letter from the Archdiocese of Milwaukee’s superintendent of schools. He wrote: “As Superintendent of Schools…I am obligated to issue an order to you and your Sister Principal not to participate in the boycott.” In response, all the schools, except St. Boniface, agreed not to use their facilities as Freedom Schools.

The following day, Father Bleidorn received a letter from Bishop Roman Atkielski, who was in charge while Archbishop William Cousins was in Rome. The letter stated that the city’s district attorney had decided that participating in the boycotts was illegal, therefore, “none of your parish facilities, such as your church, school, hall, gymnasiums, convent or rectory may be used for a Freedom School.”

“Everyone was praying like crazy”

Sister Marie LeClerc remembers this period was one of confusion. Bishop Atkielski had forbidden the parishes from acting as Freedom Schools, but he said nothing about individual priests or sisters participating. To make matters worse, the local newspapers were running stories about the disagreement between the pastors and the archdiocesan officials. It seemed that one day the papers would report that the parishes received permission to participate and the next day they would say the opposite.

For example, on Saturday, October 16, 1965, the Milwaukee Sentinel published an article stating that Bishop Atkielski had “expanded an order by the Catholic school superintendent to say that no priests, nuns or brothers are to participate in any way in the scheduled public school boycott.” However, none of the pastors or sisters had received any official directives forbidding them from participating. Father Bleidorn explained their position: “We took our guidance from the official communication to us, not from an unofficial interpretation in the daily press.”

The priests knew that the Sunday newspapers would want a statement from the parishes and schools about whether or not they were going to participate. Because they had been receiving conflicting information, a group of priests, sisters and lay persons, including a lawyer, met at St. Benedict the Moor to draft a statement. A tentative press release was drafted and Father Matthew Gottschalk called Bishop Atkielski to read him the press release. When Father Gottschalk went to make the call, everyone was “praying like crazy,” Sister Marie LeClerc remembers.

Father Gottschalk returned to the group and said the bishop suggested two changes and agreed that they could release the statement. According to an unpublished timeline of events found in Sister Marie LeClerc’s papers, “All priests and sisters present interpreted this to mean clearly that the Bishop is now permitting each priest and religious to follow his own conscience in the matter.” The priests released the statement.

The tone of this press release differed from previous ones. The priests reiterated the facts about school segregation and the problems it caused. However, this time, they spoke more about their own conscience and the reason they felt they needed to act. They wrote that they respected the archdiocesan authority, but “in our own conscience, we do not see his directions based on legal opinion at this time as morally binding with the force of Christ’s words. Rather, we consider that Christ’s call, coming to us through His poor, requires us to act otherwise. In doing so, we do not, and we so solemnly declare, consider we are disobeying Christ, but rather obeying Him, speaking through another voice in these trying circumstances.” They ended the statement by affirming that they would “accept children who come to us to be taught in Freedom Schools in this serious crisis.”

After the meeting, Sister Marie LeClerc called Mother Antonice Murawski, the local SSND provincial. Mother Antonice worried that the sisters would be arrested, but she acknowledged that while she didn’t understand the situation in the inner core as well as the sisters, she trusted them to do what they thought was best. Sister Marie LeClerc later said that Mother Antonice’s support meant a lot to her and the other sisters, because she respected their right to make decisions based on their own conscience and experiences working in the inner core.

On Sunday morning, the statement was printed in the newspapers. From the pulpit, the pastors praised the archdiocese for allowing them freedom of conscience on this issue. However, at noon, Monsignor Brust, chancellor, came to St. Boniface and asked Father Bleidorn to “avoid undue scandal to the Church.” Meanwhile Bishop Atkielski said publicly that he had not authorized the release of the statement. At 3:30 p.m., the priests from St. Francis, St. Benedict the Moor and St. Elizabeth issued a press release stating they would obey, and two hours later a second statement was released by the pastors, this time including Father Bleidorn, stating the same.

However, the second press release also included a statement about the bishop and the archdiocesan hierarchy: “It was with great joy that we received his [Bishop Atkielski’s] statement. We thought that the church in Milwaukee was being given the historical distinction of being the first place in our country where a bishop would apply in a specific case the declaration of freedom of conscience as enunciated just a few weeks ago in Rome by Vatican II. It seems we have overestimated the situation.” They closed the statement by saying, “With every protest short of direct disobedience, and with some conviction that we are substantially betraying our people, but with the hope that we might be wrong, we revert to the basic training we have been given and reluctantly close our parish facilities to the use of the freedom schools.”

That same evening, Bishop Atkielski went on television and when asked whether or not priests and sisters were authorized to participate in Freedom Schools, he replied, “The chancery has not authorized any action and the participants are exposing themselves to ecclesiastical consequences which will be related in detail to the Archbishop the first time we can get in touch with him.”

It had been settled – St. Boniface would not act as a Freedom School. However, the issue of whether or not individual priests and sisters could participate had not yet been settled, so on Monday morning two sisters from St. Boniface left to teach at a Freedom School. Father Bleidorn and Sister Marie LeClerc wanted their students to experience the Freedom Schools so those children who received parental permission would be bussed to a participating school. Students who did not get permission stayed behind and the remaining sisters stayed at St. Boniface to teach their regular classes.

“It felt like a betrayal”

On the morning of the boycott, approximately 300 children gathered outside of the school. There was a mix of St. Boniface students, who were waiting to catch a bus to a Freedom School, and neighborhood children who had not received the message that St. Boniface would not act as a Freedom School. To make matters worse, the busses that were supposed to take the St. Boniface students to another facility did not arrive, but television cameras and reporters did.

Father Groppi and Sister Marie LeClerc went outside to talk to the children and told them that St. Boniface could not open as a Freedom School. She said telling the students that they couldn’t come in was the hardest part, because it felt like a betrayal on their part and on the part of the Catholic Church.

In order to stall until other arrangements could be made, Father Groppi led the children in freedom songs and marched the older students around the block. According to a newspaper account, he later mounted the steps of the church and said, “You know we can’t have a freedom school at St. Boniface today. I don’t know where they will be. But until we get something arranged we’ll sing out here.” Father Groppi kept the older kids busy for a few hours, before walking them to a Freedom School a few blocks away. He then spent the next two hours teaching the students African American history.

Meanwhile, Sister Marie LeClerc went to work sorting out the children who had permission to attend a Freedom School from those who were to stay at St. Boniface. She also took time to speak to parents and comfort the children who were anxious because they didn’t know where to go. The scene may have looked chaotic, but Sister Marie LeClerc said that things were under control. She took care of the younger children until transportation arrived.

Meanwhile, Sister Marie LeClerc went to work sorting out the children who had permission to attend a Freedom School from those who were to stay at St. Boniface. She also took time to speak to parents and comfort the children who were anxious because they didn’t know where to go. The scene may have looked chaotic, but Sister Marie LeClerc said that things were under control. She took care of the younger children until transportation arrived.

Sister Marie Leclerc later wrote in the St. Boniface chronicle, “Nation-wide coverage publicized our obedience as defiance. Father Groppi merely led the great number of children off our grounds to churches of other denominations that accommodated our students…St. Boniface was on the National CBS News two days.”

The boycott lasted three days, making it the longest school boycott in American history to that point. This controversy within the Archdiocese of Milwaukee made national news, which brought attention to the boycott. However, it shifted the emphasis away from the segregation that existed in the public-school system and more toward a debate about the role of clergy in civil disobedience.

When asked to reflect upon her participation in the boycott, Sister Marie LeClerc said that the situation was tense. She felt that they were surrounded by people who didn’t understand what they were trying to do and thought we were being disobedient. She said the media and those who didn’t support the boycott portrayed them as something they weren’t. She received some hate mail and phone calls during this period. She didn’t keep the hate mail, but she remembers people sending postcards with words cut out of newspapers and magazines calling her obscene names and using racial slurs. In an anonymous letter dated October 18, 1965, the writer asked why the sisters had to be involved in “this trouble.” The author stated that St. Boniface allowed black children into “our” church and school, so “why do you and this radical priest Father Groppi have anything to do with this…We always taught our children to obey, there are laws of our church and also of our country, which is being torn down with all this trouble…God have mercy on all of you.”

“No one said it was going to be easy”

Sr. Marie LeClerc remained faithful by praying and trusting in God. She said the sisters prayed a lot and were convinced that this was the social justice issue of their day and they took part in it because they chose to do so. Some of her favorite memories of the boycott occurred when she received letters from sisters hundreds of miles away who said that they didn’t necessarily understand what the sisters were doing, but they supported their decisions. One sister wrote, “I still remember, and will never forget, the lesson of courage and love which you and your sisters gave last weekend. I will remember it as a lamp in some darkened room and I shall hold it high in my hand against whatever darkness. I pray for your continued courage in these trials and causes which you bear for Christ and his poor.”

In 1966, Sister Marie LeClerc had finished her six years as the superior at St. Boniface, but her work with underserved populations did not end there. Her next position was director of the SSND Head Start program at St. Michael, St. Boniface, St. Elizabeth and St. Francis Catholic Schools. She then served as principal at St. Joseph Home for Emotionally Disturbed Boys in Green Bay for five years before working as a junior high and high school teacher at St. Mary’s High School in Menasha, Wisconsin. Sister Marie LeClerc then returned to Milwaukee where she spent the next six years teaching at Bruce-Guadalupe Community School.

In 1986, Sister Marie LeClerc started a new ministry as the curriculum and volunteer coordinator for the Milwaukee Achiever Program, an adult literacy program. After six years with the program, she took a sabbatical and then served on staff at Divine Savior / Holy Angels High School and she taught adult English learners at Milwaukee Area Technical College in the evenings. From 1996 to 2004 she taught at Milwaukee Achieve and she retired in 2009.

When asked if she could ever imagine the direction her career would take, she laughed and said she was from “little Menasha.” However, her years working in Milwaukee’s inner core and with other underserved populations taught her the importance of getting to know people. She advised that it is easy to listen to stereotypes and to fear people you don’t know, but it’s direct contact that really teaches you that everyone is a human being that is loved by God. She said it’s a hard job, but that is what Christianity is about – “no one said it was going to be easy.”

Sources:

- Sister Marie LeClerc Laux, oral history interviews, 1982, 2008 and 2019.

- Sister Marie LeClerc Collection, School Sisters of Notre Dame North American Archives, Milwaukee, WI.

- Records from St. Boniface, St. Francis and St. Elizabeth Schools, Milwaukee Province Collection, School Sisters of Notre Dame North American Archives, Milwaukee, WI.

- “The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee,” by Patrick D. Jones.

- “Lessons from the Heartland: A Turbulent Half-Century of Public Education in an Iconic American City,” by Barbara J. Miner.

- “March on Milwaukee,” digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries and the Wisconsin Historical Society: https://uwm.edu/marchonmilwaukee/

- Sister Marie LeClerc Laux read and made corrections to this article. During her corrections, she added information that wasn’t included in the three oral histories, especially about the events of October 18, 1965.