The School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) have opened academies, institutes, high schools and colleges which have offered a high-quality education to thousands of young women. This month, the 175th celebration of SSND in North America highlights some of the unique traditions, sports and celebrations at several of these schools in the United States and Canada. This is a small sample of schools sponsored by the congregation.

Did you know that SSND established the first Catholic college for women to award the four-year baccalaureate degree in the United States? Have you ever heard of a sport called tennequoit? Have you ever listened to a song about slate steps? Curious? Read on to learn more about what makes SSND schools unique.

Calling All Alumnae

The staff at the North American Archives (NAA) would love to hear from you! Please share your memories from your time at a SSND school. Tell us about your favorite event, teacher, tradition, memory or general thoughts about your time there. Staff would like to collect these stories for the archives. Please send your stories to archives@ssnd.org.

The NAA is also interested in donations of materials that may have been collected while a student at a SSND school. We will gladly accept photos, yearbooks, copies of the school newspaper, scrapbooks and other ephemera (such as playbills, graduation or event programs, etc.). If you have something you would like to donate, please contact us at archives@ssnd.org or 414-763-1000.

Honors Day

by Michele Levandoski, Archivist

On September 6, 1875, the Academy of Our Lady (AOL) in Longwood (now Chicago), Illinois, opened its doors. In the 19th and early 20th century, it was common practice for SSND academies and institutes to give awards to graduates as part of the commencement ceremony. By the 1920s, the practice was either discontinued or occurred on a smaller scale, but at AOL, the tradition continued in a different form known as Honors Day.

In the 1920s, the number of AOL graduates had grown large enough that commencement could no longer be limited to a single event. Instead, prior to graduation, seniors enjoyed a week of activities including Farewell to Seniors, hosted by the junior class, a Baccalaureate Day, Mothers’ or Parents’ Day and Field Day. Many of these traditions faded through the years, but the one that remained constant was Honors Day.

It is not known exactly when the first Honors Day was held, but in 1929, the school chronicle mentions that during the last assembly before graduation, awards and prizes were given out to leaders in scholarship, religious activities and athletics. The first time the name Honors Day showed up in the school chronicles is 1934.

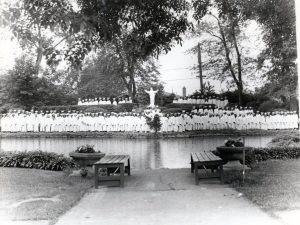

The events described in the 1934 chronicle continued for the next several decades. A few days before graduation, seniors, wearing their white caps and gowns, would march double file from the administration building to the lagoon. There, the seniors gathered in front of the Shrine to the Sacred Heart while the other students lined up around the lagoon. The chaplain would read the Act of Consecration to the Sacred Heart, which the students repeated once he finished. The graduates then processed to Hackman Hall where the awards were distributed. The assembly finished by singing the school song, “Fair Longwood.”

Seniors were awarded pins, keys and other symbols of accomplishment for outstanding work in scholastics, departmental awards, services awards and honors for things like perfect attendance. In later years, the program also featured the presentation of college scholarships to graduates.

The last Honors Day program was held in 1999 for the last class to graduate from AOL. It was tradition for seniors to be inducted into the Alumnae Society during the Honors Day ceremony, but at this last event all students were inducted as AOL alumnae.

Tennequoit

by Elizabeth King, Class of 1969

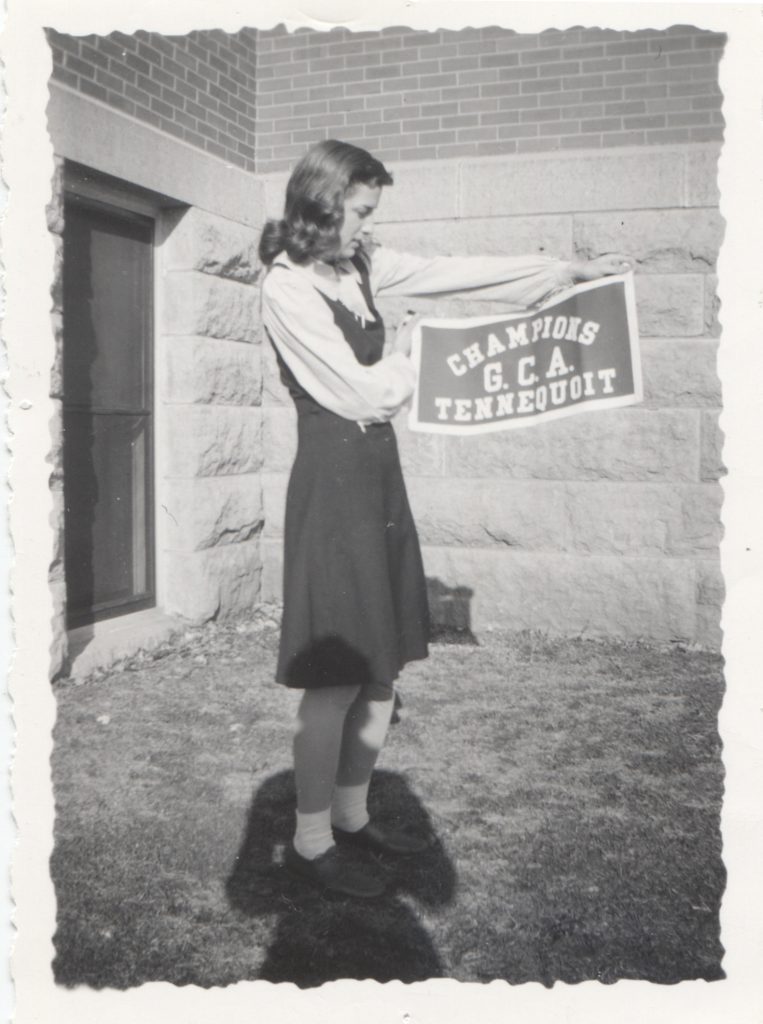

The first game of tennequoit was played at Good Counsel Academy (GCA) in 1932. The game was chosen to replace the relay races as part of the physical education program. An article from a 1932 copy of Echoes, the school newspaper, stated, “The girls have taken an active interest in the game so far,” which must have held true as it was still played when GCA closed its doors in 1980.

Tennequoit is a sport played on a tennis-style court with a rubber ring tossed over a net that separates the opponents – much like volleyball; except only one person catches the ring with one hand. From the point of catch, using that same hand, the ring is immediately returned to the other side. Points are scored only by the serving side when the opposing side fails to keep the ring in play. When the serving side misses, either by failing to get the serve over the net in two tries or missing the return of the ring, the serve moves to the other side. The team to reach 15 points first wins.

The finesse of the game came with the speed at which the ring was tossed, as well as the spins and turns accomplished by how the ring left the hand of the thrower. A healthy number of conversations took place as to where to land a throw, and how to get a great spin on the ring in order to best the opposing side!

The origins of the game are unclear, with some claiming a German origin. A more immediate ancestor is likely the game of deck tennis, a common physical activity played by teams at the beginning of the 20th century on cruise and military ships. Initially, the rings were made of rope and gradually moved to rubber, which is still used to this day.

GCA tennequoit team, 1954. Mary Jo (now Sister Paulette) Pass is pictured with the tennequoit ring “halo” over her head.

Ask any Good Counsel graduate and they will know the sport of tennequoit. That would not be the case with most of our family and friends. “I’ve never heard of that,” was, and probably still is, more often the response.

However, internationally, more than 90 years after GCA played its first game, the fifth Tennequoit World Championship is being planned. The rules are much the same, although in competition it is now played as singles or doubles, instead of the original teams. The first national championship game was played in 1929. After that, little information is found until South Africa and India hosted a national championship in 1960. In 2004, the World Tennequoit Foundation was started, now hosting the occasional championship event.

Personally, I played on our class team during my junior and senior years. We played against the other grades. Funny the moments remembered. One was playing against the seniors when I was a junior, and the juniors won. But the glory wasn’t in defeating the seniors, but winning over Mary Ann Kuhn – now Sister Mary Ann, SSND! She was so good, and a very competitive player.

Tennequoit was a game of physical fitness, but as in many things in life, it is the other lessons that stay long after the game: being a member of a team, assessing what moves are successful and make a difference (and do more of those), celebrating the wins and the opportunities to participate, and even staying in touch with those fellow teammates long after the game has ended.

Where a Gateway Opens

by Sister Barbara Brumleve, former coordinator of Mission Integration

Incoming freshman processing through the school’s iconic Gateway, 2022. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame Preparatory, Baltimore, MD

Each September, all new Notre Dame Preparatory (NDP) students process through the school’s iconic gateway while older classmates form an honor guard and sing the alma mater, which begins, “Where a gateway opens to Our Lady’s way.” Later in the school school year, after graduation, NDP’s newest alumnae, clad in white dresses and carrying red roses, process outward through that same gateway as young women educated and committed to transform the world. These two simple, yet meaningful community traditions anchor the school year and remind all of the history of NDP and its founding order, the School Sisters of Notre Dame.

The story of the gateway goes back more than a century to 1887 when Notre Dame of Maryland Collegiate Institute for Girls, founded in 1873, erected a wooden arch over its main entrance on Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland. By the summer of 1892, the wood had decayed beyond repair inspiring the school to erect “a handsome gateway, consisting of grey stone pillars … at the main entrance to the grounds.”

2022 graduates walking through the Gateway for the final time. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame Preparatory, Baltimore, MD

Over the next 70-plus years, that arch stood. If it had a voice, it could have told of the college of Notre Dame of Maryland emerging on Charles Street; of Notre Dame Preparatory School outgrowing its space as day students outnumbered boarders; and of boys—always few in number—no longer accepted in the lowest grades. In 1960, the arch witnessed faculty, students, and NDP families moving the secondary and elementary schools to Hampton Lane.

Then, in 1971, the unexpected happened! A student’s car hit the supporting pillars, damaging the arch and knocking it loose. The arch was removed and disappeared for 25 years. In 1996, surveyors at the college working on a master plan to stop erosion noticed a piece of arch among the leaves and debris. After identifying it as part of the 1892 arch, the college displayed the artifact, and then stored it until future restoration.

When NDP’s Gateway newspaper staff learned about the arch, they proposed to Sister Christine Mulcahy, then-NDP headmistress, the idea of installing a similar structure on Hampton Lane. In their November 18, 1998, issue, student journalists advocated that the gateway was “a meaningful part of NDP’s history,” as gateway was the name of the student newspaper and was referred to in the school song. Four years later, student support prevailed. The Class of 2002 adopted installing a replica gateway as its senior gift to NDP, raising more than $21,000 from 111 donors, most of them senior parents. In addition, NDP’s class of 1955 gave $1,200 for the archway project, a gesture that figuratively connected the two campuses through this shared symbol (Notre Dame of Maryland University also installed an archway on its campus in the fall of 2015).

It was Sister Christine who launched the beloved tradition of walking through the gateway when she invited the Class of 2002 to be the first group of graduating seniors to walk through the gateway away from the school. The following September, she invited new students to process through it toward the school. As she reflected, “I never would have dreamed of it, if the girls hadn’t gone after it.”

Remembering Notre Dame Academy in Waterdown, Ontario, Canada

by Sister Joan Helm, Principal 1973-1978

On May 19, 1933, 50 former Notre Dame Academy (NDA) students returned to Waterdown, Ontario, to attend a weekend house party and hold an organization meeting of the “Convent Alumnae.” The alumnae spent the weekend in various activities, including playing bridge, attending a dance, hiking, Mass in the convent chapel and visiting favourite haunts of former years. On Sunday, the women planted a maple tree to mark the first reunion of students of NDA.

With the opening of the Canadian Motherhouse on February 14, 1927, Notre Dame Academy welcomed student boarders from Mexico, Trinidad, Jamaica, Hong Kong, United States and across Canada, as well as “day-hops” from nearby. Since 1933, the alumnae reunions have become an important school tradition. The reunions were held every five years and continued after the school closed in 1983.

In 1977, the alumnae reunion celebrated the 50th anniversary of the school. Sister Antoinette McCarthy, the school’s first principal, opened the celebration with a quote from poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, “May our echoes roll from soul to soul, and grow forever and ever!” She then had the honour of pouring tea. Eucharist was celebrated in late afternoon. The cross bearer and acolytes were Charlie Robbins, James Crusoe and Bill English, who were students in 1930s. Following the Eucharist was a festive dinner at which more than 1,500 former students attended.

On June 2, 2002, the 75th anniversary of the Canadian Motherhouse, another historic reunion was held. Special guests included eight grads from the 1930s.

In light of the future sale of Notre Dame Convent, June 10, 2018, was posted as the final NDA reunion. There was an amazing turnout. Students came from Belgium, Mexico, Florida, South Carolina, Iowa, Saskatchewan, Quebec and near and distant parts of Ontario. A 1942 graduate, age 92 and accompanied by her daughters, proudly announced her presence. Some groups gathered the previous evening to reconnect and reminisce; others dined together after the reunion.

To quote, “It was clear from the constant chattering, the smiles and the hugs that the women were happy to renew friendships from school years.” Viewing yearbooks, photo albums, the five different styles of uniforms through the years, graduation photos on the screen, and reading the graduate dance requests that listed the graduate and her dance song (songs like “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” “Stranger in Paradise,” and “Moon River” in 1964) – all nostalgic moments!

Emails received after the event included comments such as: “NDA was such a fertile place for learning and fun”; “There is a very strong sisterhood among NDA girls and their teachers”; “NDA has always been a community home”; “The impact of NDA still lives on today knowing that the hand of God is visible and the dedicated work of the Sisters is appreciated.”

In an article published in the local paper prior to the reunion, Louise Ann Caravaggio, class of 1983, wrote, “Notre Dame Academy was more than just a building; it was a place that helped young girls become the women that they are today and gifted them with important core values – a sense of empowerment and the love of learning.”

Feast Day

by Michele Levandoski, Archivist

AHA students ordained as Eucharistic Ministers at the 2022 Feast Day Mass. Photo courtesy of the Academy of Holy Angels, Demarest, NJ

On October 2, 1879, Sisters Nonna Dunphy and Cyrilla Giefel signed the deed for a house and property located in Fort Lee, New Jersey (the school moved to Demarest, New Jersey, in 1965). The contract was signed on the Feast of the Holy Guardian Angels and the Academy of Holy Angels (AHA) took its name from the holiday. The celebration of the feast day anniversary of the signing of the deed has been an important annual event at the school.

The first mention of the feast day in the AHA chronicles occurred in 1882 when the Bishop of Newark made his first visit to Holy Angels. “Being already a feast of the institution which is dedicated to the Angels, the day was made both more solemn and joyous by the presence of the Bishop,” who was entertained by the children for two hours with singing and speaking.

The tradition of celebrating the feast day continues to this day, although the way in which it is celebrated has varied greatly throughout the years. In 1915, the school “celebrated the school holiday with a trip to the National Biscuit Factory and to see ‘U-need-a’s’ made and baked and packed and shipped.”

The celebration of the feast day also changed in accordance with the growth of the school. In 1925, a sister wrote, “Oct. 2 was our first holiday and we spent the day quietly at home contrary to our usual custom but the school is getting too large for those family-like excursions of some years back.” The nature of the celebration changed, but it remained an important part of the school’s academic year.

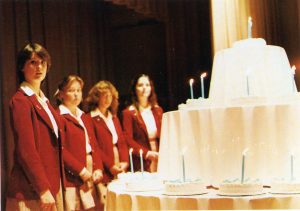

One of the largest feast day celebrations occurred as part of the schools 100th anniversary. On October 2, 1979, students sat in the auditorium and watched as the curtains parted to reveal a replica of a large cake that revolved on a table. Surrounding it were several small cakes, each of which had a lit candle. The students sang, “Happy Birthday,” then the class representatives went on stage and received a cake for her class. The principal, Sister Norice Sullivan, also gave the faculty and students a small crystal angel as a souvenir.

Today, the feast day on October 2 is celebrated with Mass, the installation of Eucharistic Ministers and ice cream treats for all. The singing of the alma mater has also seen a revival in recent years. There isn’t a student, teacher or alumni who does not recognize “Blaze in deathless glory.”

Fall Festival

by Michele Levandoski, Archivist

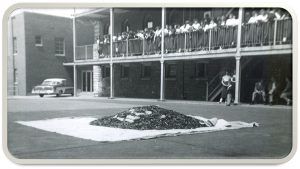

Students looking at their collection of pennies from the Million Penny Drive, 1955. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame High School, St. Louis, MO

In 1934, the St. Louis Motherhouse aspiranture became Notre Dame High School (ND), which was open to both lay students and aspirants. Classes were originally held at the Motherhouse, but by 1955, the space was needed for other purposes. The province did not have the financial resources to build a new school, so on January 10, 1955, in an “unusual burst of teen sincerity” the students at ND launched the million-penny drive to raise money for a new building. The students teamed up in a friendly competition to see who could raise the most pennies. Four months after it was launched, the final penny drive occurred and students celebrated reaching their goal by “crowning” the student who had collected the most pennies, Mary Therese Holzen, as their official Queen of the Penny Pile.

The million-penny drive paved the way for the first official fall festival the following year and the event continues to be celebrated annually. The fall festival season kicks off with an in-school pep rally. Students dress in their class colors, choose class themes (such as Senior Sailors or Famous Freshmen) and vote for their class favorite. The rally also includes specific cheers and closes with the school song.

Fall Festival class cheerleaders performing group cheers, 2021. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame High School, St. Louis, MO

The main event is held over a weekend in either October or November. The day includes food, music, game books, activities and cheers. The cheerleaders chosen at the opening rally perform their unique cheers several times throughout the day. Fundraising is still an important part of fall fest, but instead of collecting pennies, raffle tickets are sold.

One tradition that is fondly remembered by alumnae is the middle booth. Each class decorates one side of the four-sided booth with its class color and the theme for the year. The booth is the focal point for the last school pep rally, and on the day of the fall festival, it is placed in the center of the gym. Impromptu cheers take place there throughout the day.

The final and most anticipated event of fall fest weekend is the coronation of the Fall Fest Queen. The favorite of the class that raises the most money is crowned as the queen. Historically, seniors tend to win, although there have been two documented upsets (1966 and 1989)!

During the coronation, adults sit in the gym and students line the aisle where the favorites will walk in. The class favorites are dressed in formal wear that corresponds with her class color (green for freshmen, yellow for sophomores, red for juniors and blue for seniors). They are escorted into the gym by their father or another parent. The previous year’s Fall Fest Queen is present to crown the current year’s winner. Confetti cannons go off in the class color and of course the event ends with the school song.

Notre Dame fall festival is anchored in tradition; if you have experienced it, you know it is more than just an event. It was created out of enthusiasm, spirit and the raw admiration ND students have for their school. It is an event that makes you proud to be ND!

Footprints in the Stone

by Institute of Notre Dame Heritage Room, Notre Dame of Maryland University, Baltimore, Maryland

Skirts hung on the bannister as part of the 100 Days to Graduation. Photo courtesy of Melissa Kisner

Upon entering the Institute of Notre Dame (IND), one would soon encounter its impressive main staircase, rising in an open tower from the foyer to the fourth floor. Each step was crafted from natural black slate, emitting a soft glow as if lit from within. The stairs were complemented by large, intricately carved bannisters. Lovingly and carefully, the sisters cleaned the stairs and polished the bannisters daily. As time went on, the students themselves cared for the beautiful building’s most iconic feature.

Initially, only teachers, visitors and seniors were permitted to use the slate stairs. In more recent decades, as that tradition faded, the slate stairs became the heart of the school. Generations of young women traversed those stairs in pursuit of knowledge to transform the world. When commencement ceremonies were held at the school, graduates in their white gowns descended those stairs, leaving their “footprints in the stone” as they left IND to make their way in the world. The stairs were central in marking milestone events over the decades. For 100 days to graduation, students hung their skirts and saddle shoes over the handrails. Alumnae regularly returned to school and made their way up the stairs to chapel, meetings and reunions. And those stairs staged many decades of class photos.

Trips up and down the stairs by thousands of students over the years gradually wore gentle valleys in the stone. We all grew accustomed to the feeling of those shapes under foot — and they inspired one particular IND student and her dad to capture all the beautiful symbolism of the slate stairs into a song they wrote and performed:

Class of 1945 sitting on the slate steps as freshman, 1942. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame of Maryland University photograph collection, Loyola Notre Dame Library

“Footprints in the Stone”

Words and music by Joseph Urbanski, father of Kristin Urbanski ‘06

The stairs in this old building have been worn down year by year

by the countless footfalls of my sisters who attended here.

Since 1847 my extended family have climbed the well-worn stairs of IND

We all start as little sisters, nervous freshmen, young and shy,

But little sisters soon become big sisters, by and by.

And though we graduate we still retain the memory of climbing these old stairs of IND.

If these old halls could speak I’m sure they’d have some tales to tell,

Tales of friendship, funny stories and some sadder ones as well

All the comedy and drama in the whole long history

of the girls who climb the stairs of IND.

And I wish that I could meet the girls that these old halls have known,

My sisters who have left behind their footprints in the stone.

Contented Isolation

by Michele Levandoski, Archivist

St. Mary of the Pines Academy (SMP) was unique for many reasons – it was the only SSND-owned school in the South, it attracted students from Latin America and in 1941, actress Maureen O’Hara married in the school’s dramatic studio. However, what made SMP truly unique was its location. The school was nestled on 300-acres in Southern Mississippi. To say it was located in a rural area is an understatement.

In 1937, Rosemary Knapp, class of 1939, wrote of Chatawa, “Speaking of noises—there’s the stillness of ‘after lights out’ broken by the occasional hoot of an owl or families of owls, the moaning howls of dogs in the woods, and the croaking grandpa, papa, mamma and baby frog, in the lake, pool or pond. Annoying? By no means—these give atmosphere and without atmosphere Chatawa would not be Chatawa.”

Students at SMP were given the same rigorous coursework as students at urban schools. The school also offered many of the same activities found elsewhere. Students regularly participated plays, concerts, parties, bazaars and pageants, as well as holiday and feast day celebrations. Sports, such as basketball and tennis, were also popular. In 1920, the school acquired a “moving picture machine” and Friday nights became movie night.

Sister Theresa (formerly Anthony Ann) Dietz standing with Buttons, one of the horses that lived at SMP.

However, because SMP was located in the country, it was able to provide activities that would not have been possible elsewhere. The school had a lake and a pond and rowing was a popular pastime. In the mid-1960s, a horseback riding club was sponsored by Sister Theresa (formerly Anthony Ann) Dietz. Students learned how to care for and ride the horses that lived on the property.

Mary Ellen Weaker, class of 1965, said that Sister Patrick Powers instilled in the students a real appreciation for nature. Almost every week she would take a group of students on a three- to six-mile hike. There was a rumor of a marble bathtub hidden on the property and Sister Patrick, who was a SMP graduate herself, was always game to take the students on a hunt for the elusive bathtub.

Of course, country living did have drawbacks. In 1921, a severe storm washed away the bridges and the school’s phone lines were out of commission. A sister later wrote, “We are entirely shut off from the outside world.” If the power went out, it was not unusual to see students carrying buckets of water from the swimming pool to the various lavatories. Although not common, occasionally the outside came indoors. For example, in 1937 the music and French classes were surprised when a chicken wandered into their classroom!

Chatawa was a unique location that afforded students a unique education. Mary Ellen remembers the peacefulness of the area that had few distractions when compared to an urban school. However, Rosemary summed it up best when she wrote in 1937, “In short, Chatawa is a place of happy, contented isolation; but, under no circumstances, of desolation.”

A Tradition of Firsts

by Michele Levandoski, Archivist

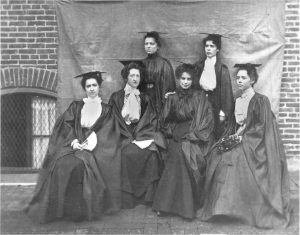

The first graduates of the College of Notre Dame, 1899. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame of Maryland University, Baltimore, MD

On June 14, 1899, the first six graduates of the College of Notre Dame received their degrees, making them the first women to earn a bachelor’s degree from a Catholic college in the United States. The college, now Notre Dame of Maryland University (NDMU), was an outgrowth of the Notre Dame of Maryland Collegiate Institute, which was founded in 1873. In 1895, the decision was made to open a college on the same property, which makes NDMU the first Catholic college for women to award the four-year baccalaureate degree in the United States.

Since 1895, NDMU has had a tradition of firsts that make it unique in both the history of Catholic women’s higher education and amongst colleges and universities in Maryland. The school’s dedication to the education and enrichment of all women has been the driving force behind these innovations.

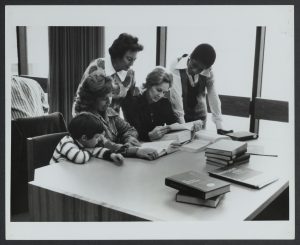

In 1972, the school introduced the Continuing Education program for women over the age of 25 or those married with a family who wanted to earn a college degree. The program grouped the women with their peers for the first year and then they attended school with the younger students in their chosen major for the remaining three years. This was the first program of its kind at a Catholic college.

Continuing Education students working in the library, c. 1970s. Photo courtesy of Notre Dame of Maryland University photograph collection, Loyola Notre Dame Library

In 1975, NDMU became the first college on the East Coast to start a weekend college program. The weekend college provided non-traditional students the opportunity to attend school on Saturdays and Sundays. The purpose of the program was to afford an opportunity to men or women whose family and work responsibilities made night school impossible.

In 1984, the university began offering master’s degrees and since then, it has established many firsts in terms of advanced degrees. In 2009, the university opened the first, and only, School of Pharmacy on a women’s college campus. NDMU is one of only two universities in Maryland to offer a doctorate in pharmacy and the only private university to do so. In 2018, the school became the first university in Maryland to offer both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in art therapy, and in 2021, it became the only private university in Maryland to offer a doctorate in occupational therapy.

NDMU has also branched out to become the first and only university in Maryland to have Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) status with the United Nations. This distinction, earned in 2015, allows NDMU students to have the opportunity to be on the floor of the UN and to participate in hearings.

NDMU has been at the forefront of change since it was founded and continues to honor its historical mission of educating leaders to transform the world.

Light of Learning

by Office of Marketing and Communications, Mount Mary University

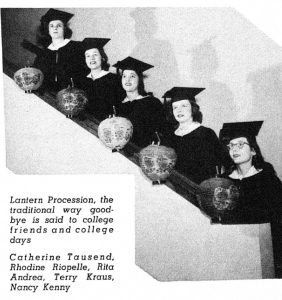

Two traditions have bookended students’ academic journeys at Mount Mary University (MMU) for 93 years: the investiture and step singing. Each ceremony shares a connection – a lantern that contains a candle symbolizing the light of learning.

Graduates and their lanterns, 1949. Photo courtesy of Mount Mary University Archives Digital Yearbook Collection

First-year students receive candles at investiture, the formal welcoming of new students into the Mount Mary community that is held annually before the start of the fall semester. Investiture is defined as a “ceremony at which honors or rank are formally conferred on a particular person,” and back in 1929, first-year students were given their graduation cap and gown at this time. They were expected to wear this attire to assemblies, formal scholastic functions and at Sunday Mass until the 1960s.

While this tradition has faded, a bit of it remains. First-year students still recite the “Cap and Gown Pledge,” written by Dr. Edward A. Fitzpatrick, Mount Mary president from 1929 to 1954. With this pledge, the group becomes part of the community of scholars at Mount Mary.

On the night before commencement, graduates are invited to pass their lanterns on to someone who has encouraged them throughout their studies. As part of the lantern procession and step singing, seniors carried Japanese lanterns and sang songs at different stops on and around the campus before ascending the steps to sing to parents, faculty and the student body. Each senior handed a lantern to a junior, symbolizing the passing on of the light of learning.

Class of 2022 walking through the Alumnae Dining Room, carrying their lanterns. Photo courtesy of Mount Mary University, Milwaukee, WI

In 1951, the tradition was memorialized in the school yearbook: “The lanterns were swayed by the kitten breezes at step-singing. We sang of our love and happy times at Mount Mary, and gave the juniors the lanterns. … Our last night at Mount Mary as students. … Tomorrow is the day!”

Portions of this tradition remain today. Graduating seniors still participate in step singing, but today they share their lanterns with significant others in their lives as they pass their lantern to a family member, friend or mentor in gratitude for their support and encouragement.

Although some of particulars have changed, the tradition of receiving and passing on the light of learning remains the same.