“All Christians and people of good will are today called to work not only for the abolition of the death penalty, legal or illegal, in all its forms, but also to work for the improvement of prison conditions, out of respect for the human dignity of persons deprived of their freedom. I would link this to life imprisonment… A life sentence is a secret death penalty.” (Fratelli Tutti 268)

This article originally appeared in the 2021 issue of Trust & Dare.

Another chance in life

Sister Jacinta Odeng began volunteering in prison ministry in 2004 as a graduate student in counseling psychology. She was greatly influenced by the movie “Dead Man Walking” and the words of Jesus from scripture: “For I was…in prison and you visited me.” (Matthew 25:35-36)

Providing both personal and group counseling to inmates at Langata Women Maximum Security Prison in Nairobi, Kenya, Sister Jacinta finds prison ministry very relevant to the School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) charism to respond to the poor but especially women and children.

Sister Jacinta Ondeng (far right) leads a group

session at Langata Women Maximum Security

Prison in Kenya

Most women prisoners in Kenya are from relatively poor backgrounds. Many confess to crimes such as child neglect, theft or assault in their efforts to provide basic needs for their families.

With less education, they are unequipped with how to resolve interpersonal conflicts and may resort to violence and even murder in an effort to defend themselves or to be understood. This can result in a life sentence; there is no death penalty in Kenya.

Sister Jacinta is motivated by her own conviction that “the human person, regardless of how broken they are, still deserves God’s love and mercy. They must be listened to, treated with dignity and given another chance in life. Imprisonment is not only about punishment but an opportunity to rehabilitate an offender so that he or she becomes a useful member of the society.”

Sister Jacinta keeps in touch with some of the women long after their release from prison. As one of Sister’s clients, Jane spent 27 years at the prison, having been sentenced to life imprisonment for robbery with violence. In December 2016, Jane was among those lucky to receive a presidential pardon. Although good news, there was no prior preparation for both the inmates and their families for their release.

Jane had not been in touch with her relatives for several years and had no immediate place to go. Sister Jacinta asked the SSND community in Nairobi to host Jane for a few days while other arrangements could be made. “The community’s ‘yes’ to my request opened our own doors of mercy to Jane, providing us with the opportunity to be Good Samaritans,” said Sister Jacinta. “Jane not only gave us an opportunity to learn from her experience, but also taught us to share love with a stranger.”

Need for love and acceptance

Sister Kathleen Eggering has worked with juvenile offenders in San Antonio, Texas, since 2004. Although not a prison, the Cyndi Taylor Krier Juvenile Correctional Treatment Center is a county facility providing residential therapeutic rehabilitation for 96 youths ages 13-17, although sometimes exceptions are made to accept younger children.

Sister Kathleen Eggering has worked with juvenile offenders in San Antonio, Texas, since 2004. Although not a prison, the Cyndi Taylor Krier Juvenile Correctional Treatment Center is a county facility providing residential therapeutic rehabilitation for 96 youths ages 13-17, although sometimes exceptions are made to accept younger children.

Sister Kathleen is the chaplain at the Krier Center. Because of the pandemic, she has been limited to offering chapel services via Zoom on Sundays and publishing a monthly newsletter. In “normal” times, she would be offering retreats for the residents several times throughout each year. “They need this because they are totally different on retreat – they let down their defenses,” said Sister Kathleen. “They’ve learned to put on hard shells just to survive.”

Having worked with children since she herself was just 19, Sister Kathleen feels called to this ministry. “These are God’s kids,” she said more than once.

Many of the youth at the Krier Center are gang members. “They’ll say it’s okay to murder because that’s all they know: poverty, neglect, abuse, abandonment, trafficking. They don’t know respect because they have never been respected,” explained Sister Kathleen.

Originally from St. Louis, Sister Kathleen joined SSND in 1954, after her junior year at Rosati Kain High School. Sister started volunteering through the prison ministry at St. Gerard parish in San Antonio, where she had served on and off for many years. This led to her involvement with Bexar County Detention Ministry, a nonprofit organization that sends chaplains into the prisons.

She is often asked, “How can you go there? Aren’t you scared?” She replies, “No! These are children who have been harmed. They need to know love and acceptance, gentleness.” Although she can’t keep in touch once the children leave the center, she takes solace in knowing she played the Good Samaritan along their journey.

Restorative justice

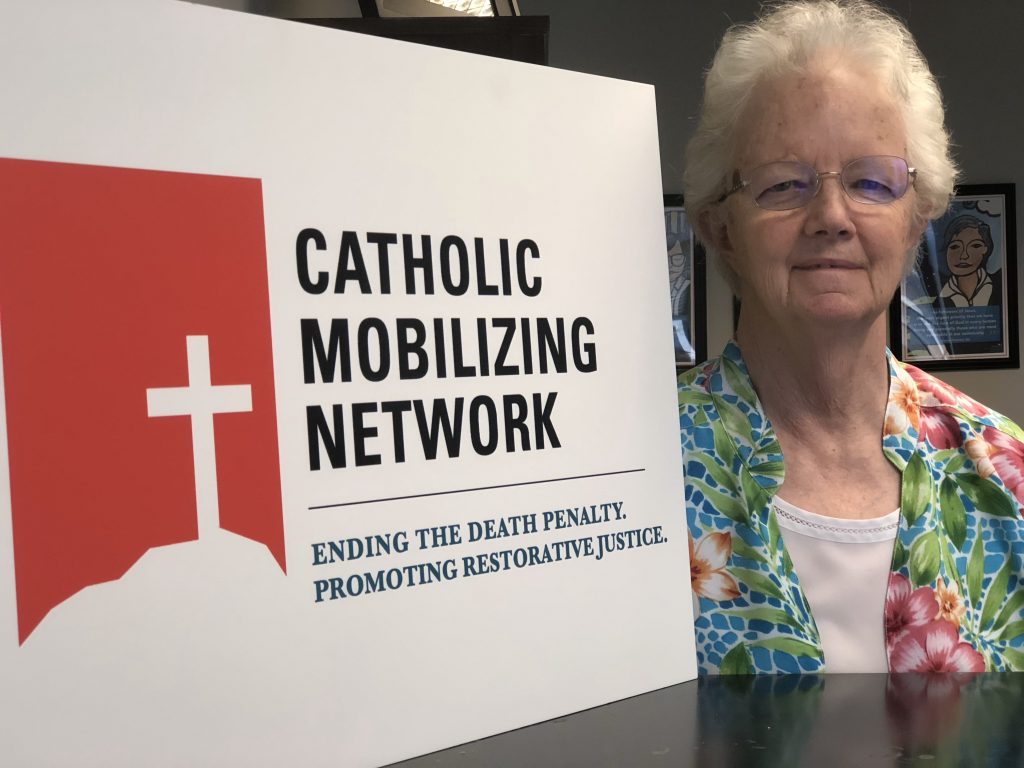

Since July 1, 2020, Sister Eileen Reilly has been a full-time staff member at Catholic Mobilizing Network (CMN) in Washington, D.C., where she works daily to abolish the death penalty in the United States. She previously had been the SSND Shalom contact for the Atlantic-Midwest province, active in efforts to abolish the death penalty in that role as well. Just prior to starting at CMN, she served as the SSND representative to the United Nations.

CMN was set up 12 years ago to amplify the U.S. Bishops’ voice against the death penalty. “Most Catholics don’t realize the bishops are against the death penalty,” said Sister Eileen. She was hired to broaden and deepen the efforts of women religious in their national efforts. “Sister Helen Prejean was one of the founders of CMN, so the contributions of Catholic Sisters are recognized and valued,” she explained.

Sister Eileen was raised in Massachusetts where there was no death penalty, so she wasn’t really exposed to it or gave it much thought. While working with Shalom, she was contacted by a man on death row. She visited him during his last six months prior to his execution in 2005. This experience “radicalized me on the issue” and was “sobering,” she said.

As an SSND, Sister Eileen has a commitment to serve the poor. “People on death row fit that category. They often have inadequate representation because they cannot afford better. The possibility for mistakes looms large,” explained Sister Eileen.

CMN promotes “restorative justice” not punitive. Instead of figuring out what law is broken, they look at how to heal the harm. This means that the perpetrator and the victim (or victim’s family) sit down together and dialogue about who is harmed and how to heal.

One recent case involved a woman whose husband was killed by a drunk driver, leaving her to raise three children on her own. She sat down with the driver to seek healing and was transformed in the process. Restorative justice helps all to be at peace.

“It takes a lot of preparation and is not taken lightly. The dialogue needs to be highly structured and facilitated. Everyone needs to be willing to enter the process. Facilitators need to think it out and play out all implications,” reported Sister Eileen.

“This ministry calls me to be very deliberate,” continued Sister Eileen. “The first instinct is always ‘isn’t that terrible, awful?’ But as Sister Helen would say, we’re all better than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”