In October 2025, all records being kept by the Academy of Our Lady Alumnae Association were moved to the SSND North American Archives. Among the many treasures that came over was a scrapbook put together by Sarah Byrne, a member of the school’s Class of 1913. The scrapbook provides a glimpse into the life of a student of this SSND school during the early part of the 20th Century.

Sarah Byrne

Sarah Byrne can be seen in the back row, second from the left, in this class photo from the Academy of Our Lady Class of 1913.

On September 14, 1912, the Academy of Our Lady, Chicago, Illinois began the school year with 230 students; 70 were boarders and the others were day students. One of those students was Sarah Byrne. She attended the school as a day student in the college preparatory program.

The scrapbook did not include biographical information, but some information about Sarah’s life has been discovered. She was born on April 7, 1895, in Chicago, to George and Alice (McGinnis) Byrne. After graduation, Sarah worked as a teacher and according to the 1920 Federal Census, she was a physical education instructor at a public school in Chicago. In 1927, she married John Dargan and the couple had two children. Sarah sent her daughter, Alice, to her alma mater. Sarah died in 1974.

Academy of Our Lady

In 1874, the School Sisters of Notre Dame founded the Academy of Our Lady (AOL) in Washington Heights, Illinois (later annexed by city of Chicago). The school was known informally as “Longwood” or the “Longwood Academy,” the name given to the area by the train station located on 95th Street and Longwood Drive. The school educated thousands of girls and young women before it closed in 1999.

A brochure for the school is pasted at the beginning of Sarah’s scrapbook. It tells us that the school included grades 1 through 8, a college preparatory or high school course, and a commercial course. Sarah was attending the college preparatory course, which was a four-year program that prepared young women for entry into “all colleges, universities and normal schools.” The school entrance fee was $5, and board, tuition, and laundry cost $150 for each of the five-month sessions. Each student was required to have three uniforms, two blue and one black; two tan and two white shirtwaists, and a white commencement uniform. “The dresses must be procured at the Academy, as they are not for sale at any other place.”

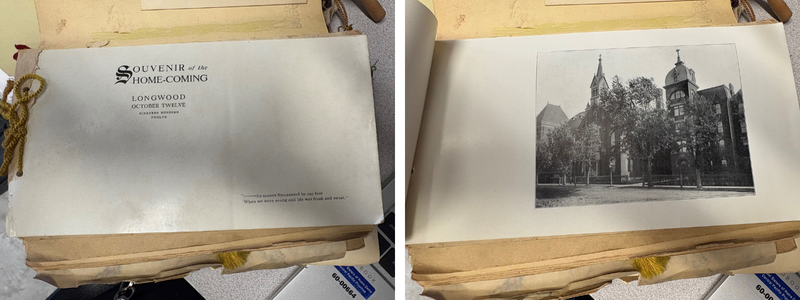

Home Coming

The souvenir booklet for home coming included a photo of the school.

Later in the scrapbook, Sarah pasted in the program for the alumnae “Home Coming” as well as the souvenir booklet. We know from the academy chronicles and the records of the alumnae association that homecoming occurred on October 12, 1912. Beginning at nine o’clock in the morning, “each train brought great numbers – others coming by cars and autos.”

The festivities began with Mass, followed by a welcome in the school auditorium. The sisters were able to accommodate the 350 women in attendance for lunch in the convent’s four dining rooms and parlor. Instead of place cards, the alumnae received a souvenir booklet that included various photos of the Longwood campus. At 2:45 p.m., the alumnae gathered in the auditorium for a “fine program” and the distribution of prizes. The day ended with a supper and a Benediction service.

According to the alumnae association records, the home coming was a “grand reunion of all former pupils of the Academy…Many, many old girls came after long years of absence and enjoyed the day program.”

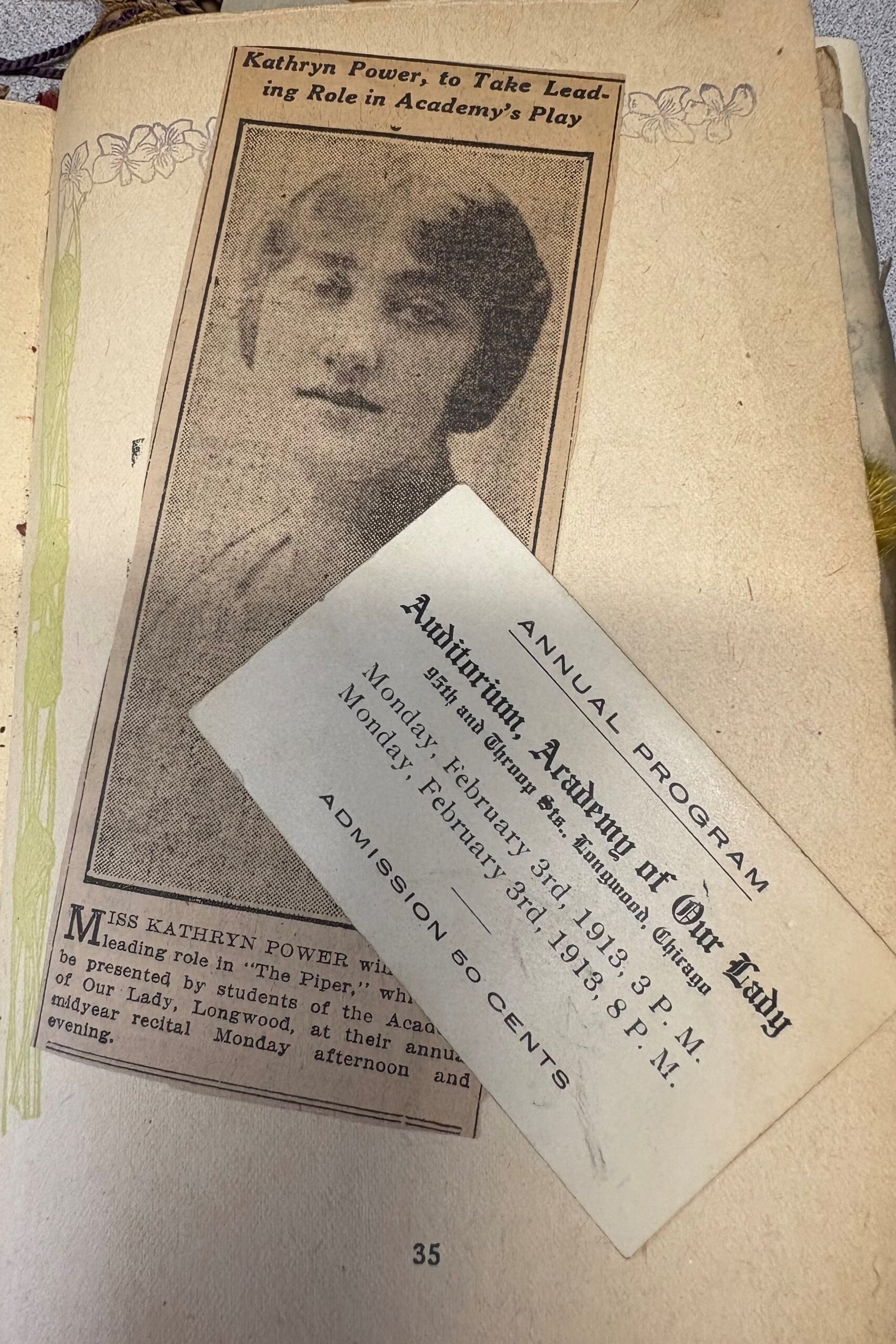

“The Piper” and the Cellist

A scrapbook page shows an article about a production of “The Piper” staged by the students at AOL in February of 1913 as well as a ticket for the show.

On February 3, 1913, the students gave an annual program with a performance of “The Piper,” based on Robert Browning’s poem, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” It appears that the entire student body, including the elementary school children, were involved in the production. Sarah played the part of “Old Ursula,” and playing the cello in the orchestra was a young woman named Zdeňka Černý.

Zdeňka was born in 1895, the second of three children of Albert Vojtech Černý and Frances Engelthaler. Her father was a successful music teacher in Chicago and her older sister, Milada, was a child prodigy in the piano. Alphonse Mucha, painter, illustrator, and graphic artist known for his distinctive “Style Mucha,” stayed with the family for several months in 1905. During the visit, he painted Milada’s portrait several times and Zdeňka asked if he would paint her as well. Mucha promised he would paint her once she became a virtuoso cellist.

In March 1913, Mucha visited the family again and he agreed to paint Zdeňka, now an accomplished cellist. Zdeňka, who attended AOL from about 1912-1914, posed for a photo with her cello and Mucha worked from this image. In June 1914, Zdeňka and her father left Chicago to tour Europe. Mucha had taken his painting of Zdeňka to a lithographer in Prague and made posters for the concert, calling Zdeňka the “Greatest Bohemian Violoncellist.” Unfortunately, the trip was cut short by the start of World War I. Although Zdeňka and her father made it to Prague, it is unknown whether she was able to play any shows before returning home.

In 1915, Zdeňka met Otto Vasak while vacationing with her father in Wisconsin. The pair eloped and their daughter, Jetta, later wrote that Otto refused to allow Zdeňka to pursue her musical career. He died in 1961 and two years later she married an old family friend and moved to California. Zdeňka died in 1998 at the age of 102, having never played her cello again.

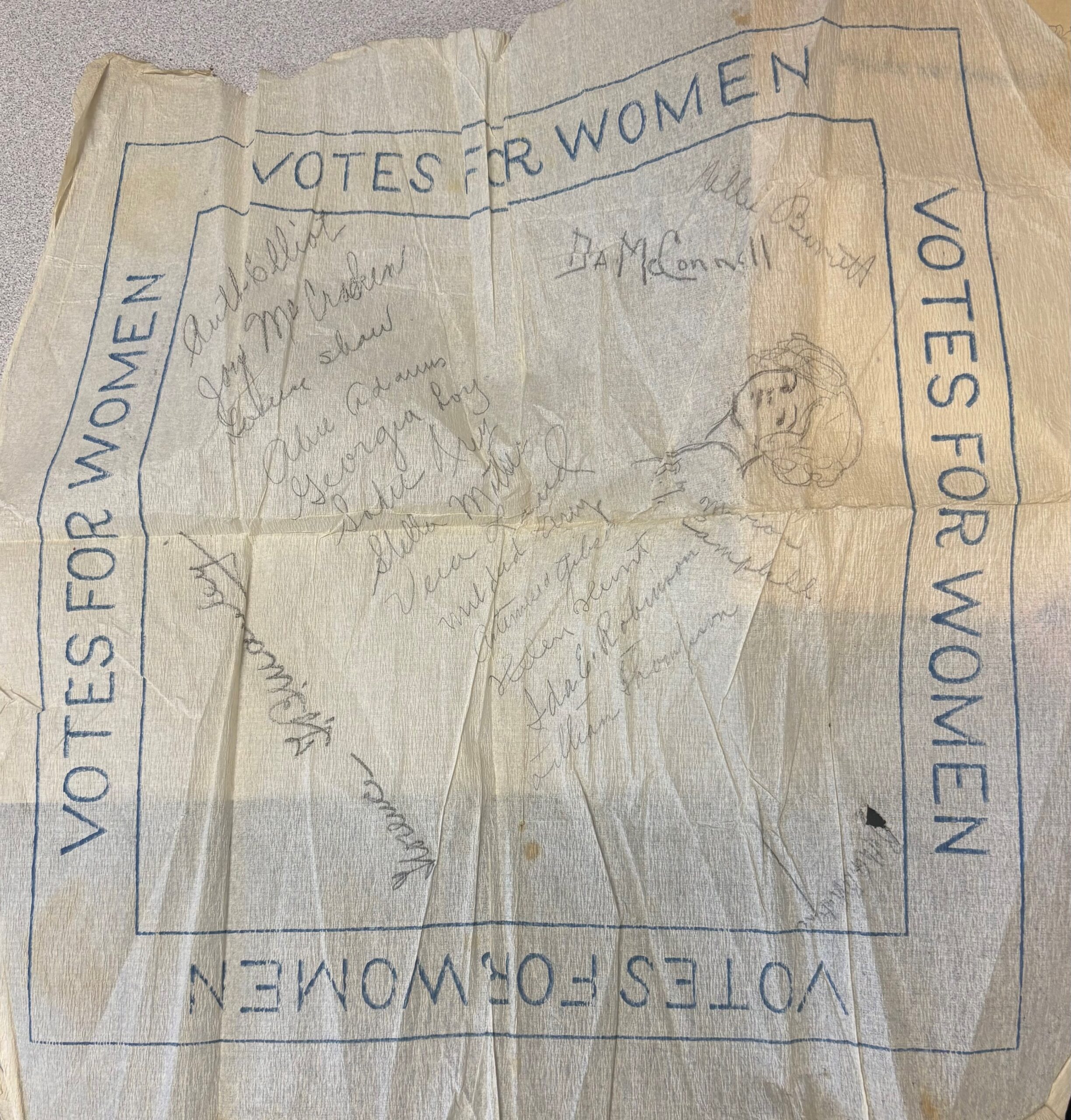

Women’s Right to Vote

A piece of tissue paper that reads, “Votes for Women” and contains a drawing of a young woman and the signatures of a number of women, possibly AOL students, connects the young women attending the Academy of Our Lady with the larger women’s suffrage movement that was taking place across the United States at that time.

In Sarah’s scrapbook is a folded piece of tissue paper that reads, “Votes for Women.” The paper included a drawing of a young woman and the signatures of several women, possibly AOL students. At first glance, it appears to be an interesting piece of ephemera but understanding the context in which it was created shows that it was part of a much larger movement.

The woman’s suffrage movement began in 1848. Initially, the movement worked to secure the right for the woman’s vote on a state-by-state basis. However, by the early 20th century, a more radical wing of the movement used civil disobedience and radical protests, such as hunger strikes and picketing, to push for a constitutional amendment.

In 1913, the National American Woman Suffrage Association organized a march along Pennsylvania Avenue, scheduled to take place the day before Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. On March 3, 1913, Inez Milholland, wearing a white dress, a cape, and a gold tiara, opened the parade riding astride a white horse. Behind her were the first of over twenty floats, followed by women organized by country, state, occupation, and organization.

Unfortunately, the parade did not go as planned. The crowd of about 250,000 people streamed into the streets and blocked the parade route. People in cars and on horseback attempted to drive people back onto the sidewalk, but the crowd was simply too large.

According to a National Park Services’ article about the parade, “the marchers found themselves trapped in a sea of hostile, jeering men who yelled vile insults and sexual propositions at them. They were manhandled and spat upon. The women reported that they received no assistance from nearby police officers, who looked on bemusedly or admonished the women that they wouldn’t be in this predicament if they had stayed home.”

The article states that despite the chaos, most women were determined to continue the march. They locked arms, ignored the threats, and in some instances used banner poles or hatpins to ward off attacks. They held their ground for an hour before Army troops arrived to clear the streets so the procession could continue.

The parade made national headlines and led to a Congressional hearing. It also energized the movement, although it would be another five years before the 19th Amendment passed, giving women the right to vote. Sarah may not have attended the march in Washington DC, but it was clear that the women who did had her support.

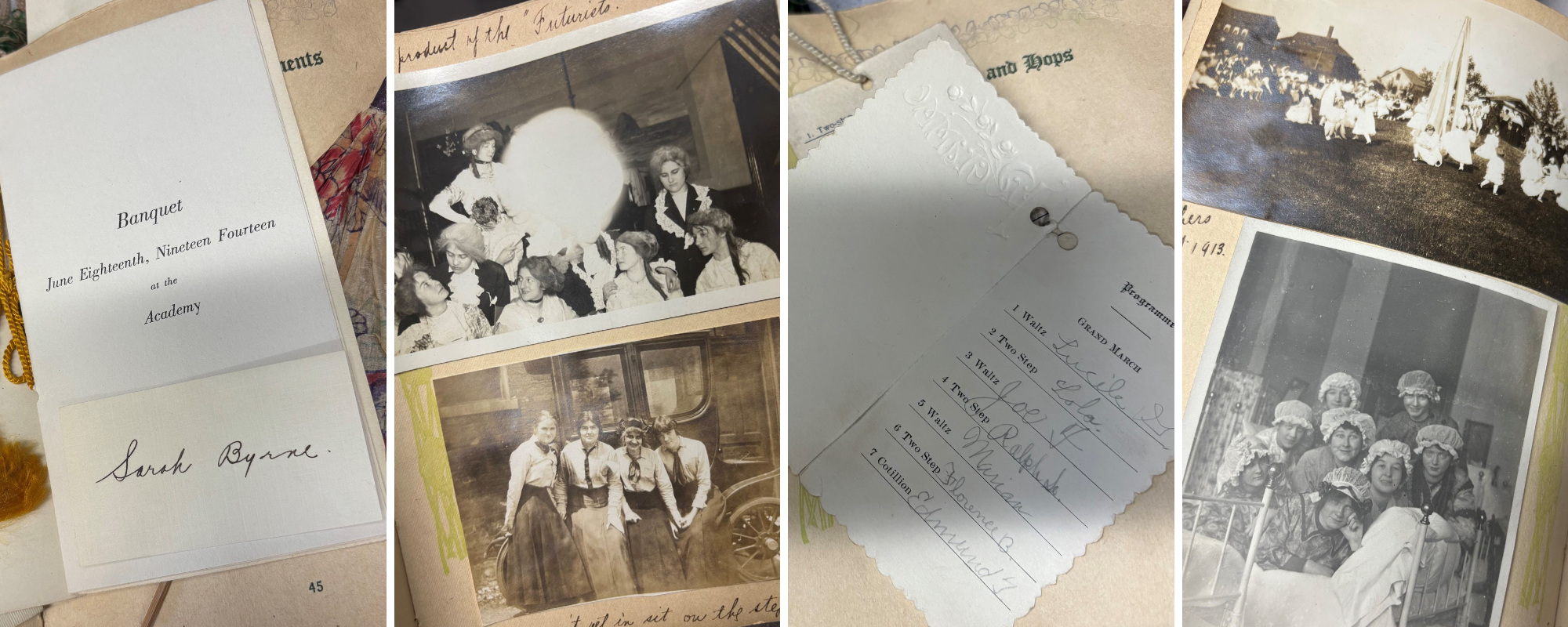

Student Life

The scrapbook is also filled with mementos and photos that documents student life at Longwood. She pasted in tickets stubs from a football game, train ticket stubs, invitations to parties, recitals, luncheons, dinners, dance cards and photos. It is clear from her scrapbook that although the sisters expected the young women to study and do well academically, there was still time to have fun.

Mementos from Sarah’s time at AOL create a picture of the social life of a student.

Graduation Day

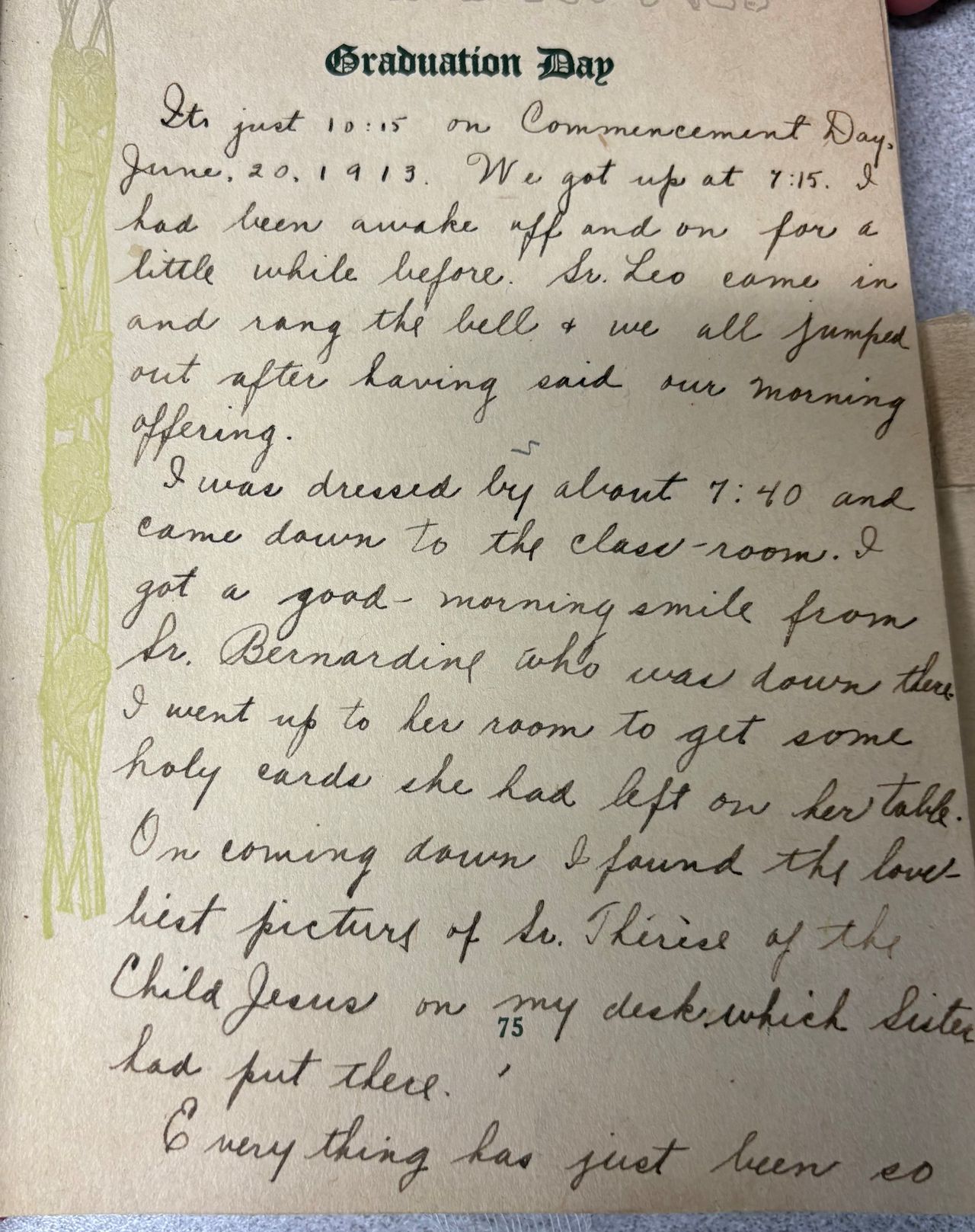

Sarah recorded her thoughts on the morning of her graduation from the Academy of Our Lady.

Sarah’s scrapbook ends with her commencement program and a written description of the day. She began with “Its [sic] just 10:15 on Commencement Day, June 20, 1913…” Her morning started when Sister Leo walked in and rang the bell. “We all jumped out after having said our morning offering.” After getting dressed, she attended Mass and “it was just lovely. I wish Sister Claretta had played the harp and then everything would be complete.” After Mass she returned to the dorm to pack and then she and two friends went out for a “little row.” At 12:30 it was time to get ready for commencement.

“Our dresses made us feel so tall and dignified and when we got our wide class ribbons on we were already to make our bows and be inspected. Although our dresses were so long and our hair done up still they didn’t make us any older and I tripped on my skirt two or three times.”

When she walked onto the stage, Sarah saw her mother and two sisters seated behind Archbishop James Quigley. After the diplomas and honors were awarded, the graduates walked to the chapel for Benediction. “We then went into the red parlor and met the Archbishop personally. He was very cordial and friendly and I remember when he put the medal around my neck he gave such a friendly and fatherly, ‘Congratulations.’”

After the festivities ended, Sarah met with her family and friends to open presents. She received an assortment of items, including kid gloves, a hatpin, correspondence cards, hairpins, and a coin purse. She ended the entry with, “…I sure received a good portion of the world’s goods that day.”