By Michele Levandoski, Archivist

Let’s begin 2023 by celebrating trailblazing School Sisters of Notre Dame. This month we highlight sisters who were the first or the only in the congregation who held certain distinctions, such as earning a Ph.D., serving as a college president or getting a chauffer’s license.

Note: Every attempt has been made to correctly identify the “first” in the categories below. However, the earliest records for SSND in North America are sparse. For some categories, it is more accurate to say that the first sister is the first sister identified as holding that distinction.

Theresia Scholl was born in 1829 in Bavaria. Little is known about her early life or how she became acquainted with Blessed Theresa Gerhardinger and the other SSND pioneers in Baltimore. What is known is that on March 25, 1848, Blessed Theresa accepted Theresia as a candidate, making her the first woman to enter the congregation in North America. Theresia spent her four years as a candidate teaching at St. James School in Baltimore. In 1852, she was accepted as a novice at the Milwaukee Motherhouse and received the religious name Clara. Four years later she traveled with Mother Caroline Friess and eight other sisters to open the first mission in New Orleans.

In June 1858, Mother Caroline made a surprise visit to New Orleans. On her trip home, the steamship on which she was travelling exploded, killing many on board. Mother Caroline survived the harrowing ordeal and had scarcely made it home to Milwaukee when she learned that there was a yellow fever outbreak at the convent and orphanage in New Orleans. Yellow fever epidemics were a regular occurrence in New Orleans. In the 1850s, the illness killed about half of those who contracted it. During the 1858 outbreak, 100-120 people died daily. In September, yellow fever made its first appearance among the sisters. On October 11, Sister Clara became ill, and two days later she succumbed to the disease.

Sister Joan Emily (formerly Honore) Kaul was born in 1925 in Watertown, Wisconsin. She entered the congregation in 1943 and spent the next 35 years working in parish elementary schools in Wisconsin. In 1974, she was assigned to Holy Cross Consolidated School in Mount Calvary, Wisconsin. It was while living there that she encountered a situation so ridiculous, it must be shared. The following was taken from a eulogy read at her funeral in 2020.

While working in Mount Calvary, Sister Joan Emily offered to drive students in a borrowed Volkswagen to the Milwaukee County Zoo for a field trip. The kids, along with parents, all travelled to Milwaukee, visited the zoo and had a great time watching the animals. When they started walking toward the car, the group was met by men from the zoo office who showed them the car, which had a bashed-in hood. They politely explained that “very unfortunately, an elephant had gotten loose and then sat on Sister’s car.” Sister Joan Emily was worried that the car would not make it back to Mount Calvary, but one of the employees pointed out that the Volkswagen’s engine was located in the rear, so the car was probably drivable. They all got in and went on their way.

When they were halfway home, they came upon an accident. Sister Joan Emily, being a kind person, pulled over to see if she could help. The people involved in the accident said they were fine and had called the police, so she set off again. About five minutes later the police pulled up behind her, so she pulled over. The police officer walked around to the driver’s window and said, “Ma’am you left the scene of an accident.” She responded that yes, she had pulled over, but the people said they were okay, so she left. The police officer replied, “Ma’am you left the scene of an accident. We call that hit and run.”

Sister Joan Emily informed him that they were not part of the accident, she had merely stopped to offer assistance. The police officer then pointed to the damaged car and said, “Ma’am you were part of the accident. Look at your car.” She laughed and told him, “Oh, you don’t understand. We were at the zoo and an elephant sat on our car.” You can only image the look on the officer’s face. He had probably heard many excuses from drivers, but surely nothing as crazy as this.

Sister Joan Emily pulled out the papers the zoo office had provided for insurance, proving that an elephant had indeed sat on the car. The officer let her go, and she and the children proceeded peacefully to Mount Calvary!

Sister Clara Scholl was the first woman to enter the congregation in North America, but she was born in Bavaria. Sister Petra Fourier Kletzlen has the distinction of being the first American-born SSND. Elizabeth was born in 1830 in Butler, Pennsylvania, and she entered the congregation in October 1848. In 1852, Mother Caroline Friess sent Novice Petra Fourier and candidate Frances Mueller to open the new mission at Mount Calvary, Wisconsin.

The people living in Mount Calvary suffered from extreme poverty. The sisters lived in a log cabin that was 16 feet by 20 feet. According to her obituary, the house was so small that the few pieces of furniture in it had to be moved aside if anyone wanted to enter. There was no drinking water near the home, so the two sisters had to go down into a valley for water, which they then carried to their home. Although local women brought food when they were able, the two women often dined on only thick milk and bread. In 1853, Sister Petra Fourier transferred to the Milwaukee Motherhouse for a year of novitiate and returned to Mount Calvary the following year. Despite the poor beginnings, Sister Petra Fourier remained at Mount Calvary serving as the superior until her death in 1920 at the age of 90.

Sister Petra Fourier also holds another distinction within the North American community. In April 1851, her biological sister became a SSND, making them the first siblings to enter the congregation in North America. Catherina Kletzlen was born in 1836 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As a candidate, she taught in Buffalo, New York. When she became a novice she moved to the Milwaukee Motherhouse, where she received the religious name Stanislaus. Sister Stanislaus’ short life was marked by new beginnings.

In 1854, Sister Stanislaus and a candidate opened the mission at Holy Trinity School in Milwaukee. Since there was no convent for the sisters, the two women were required to walk the three miles from the Milwaukee Motherhouse to Holy Trinity every morning and every afternoon. Mother Caroline Friess was concerned about this daily trek because anti-Catholics groups made it unsafe for sisters to wear their habits in public. To ensure their safety, Mother Caroline bought a “bus,” which she painted black. According to the school’s chronicles, “wags of the time were not slow in naming it ‘Noah’s Ark’ or ‘The Sisters' Black Maria’ [Black Maria was slang for a police vehicle used to transport prisoners].” In 1859, Sister Stanislaus was sent to open St. Joseph’s Orphanage in New York and in 1869, she was sent to serve as superior of Ss. Peter and Paul School in St. Louis. She died there in 1878 at the age of 42.

Beginning about the 1920s, it was common practice for women entering the congregation to write an autobiography. It is very rare to find autobiographies for sisters who lived in the 19th century. Sister Paterna Wilhelm is an exception. After her death in 1905, the sisters at St. Peter’s Orphanage in Newark, New Jersey, found her little notebook in which she had written about her life. It was transcribed into the convent chronicle. It reads:

Photo by Tim Foster on Unsplash

“Born Sept. 4, 1846, at Williamburg, Canada. After my First Holy Communion, I helped my dear Parents. At the age of 24 I entered the Candidature at Milwaukee where I received a hearty welcome from our dearly beloved Mother Caroline, as I was her first candidate from Canada. I received the Holy Habit Aug. 23, 1871. After three years, I pronounced my First Holy Vows, and in 1881 I had the happiness of pronouncing my Final Vows. My first field of labor was to teach the little boys at Elm Grove (Wisconsin), then to St. Joseph’s Parish, Washington, D.C. Since August 1879, I have been at St. Peter’s Newark, N.J.”

In 1905, Sister Paterna underwent surgery and according to the chronicle, the doctor removed 475 gallstones. The surgery was successful, but infection set in and within a few days she was gone. In her obituary, she was described as a gifted teacher who provided her students with an outstanding foundation in reading, religion and arithmetic.

Believe it or not, two families gave seven daughters to the congregation!

George and Mary (Marx) Hackenmueller have the distinction of being the first parents to provide seven daughters to the congregation. The two oldest daughters, twins, entered in 1877 and were given the names Sisters Gudelia (1859-1886) and Jacunda (1859-1928). They were followed by Sisters Lybia (1857-1936), Balthasara (1861-1943), Gudelia (1863-1897) and Johanna de Britto (1866-1929). When the seventh daughter entered the novitiate in 1888, it was clear that Mother Caroline Friess decided to have a little fun. The young woman was given the religious name Septima (1869-1955), which is Latin for seven!

Not to be outdone, Valentine and Mary Gonnering also gave seven daughters to the congregation. Sisters Ceddona (1872-1948) and Cimberta (1873-1962) were the first to enter in 1892. They were followed by Sisters Clarita (1876-1956), Honorine (1874-1938), Leonore (1880-1954), Petronilda (1882-1955) and Rosaline (1888-1973).

Throughout our history, 137 sisters have lived to be at least 100 years old (131 deceased sisters and seven living sisters)!

The first sister to live to 100 was Sister Valena Lehmann. She was born in 1861 in Formosa, Ontario, and entered the congregation in 1881. She spent the next 81 years serving as a homemaking sister at convents in Iowa, Wisconsin and Illinois. In honor of her 100th birthday, the Milwaukee Sentinel published a half-page article about Sister Valena, which included her words of wisdom for the public, “Whatever happens, you have to make the best of it. You’re not going to get an easy chair to sit there—life is not so easy.” Sister Valena died on October 6, 1962, at the age of 101.

Sister Cecile Amore has the distinction of being the longest-lived SSND in North America. Sister Cecile was born in Italy in 1905. As a child, she begged her mother for a piano but was told they could not afford it. A few years later Sister Cecile became ill. Her mother promised her if she got well, she could get a piano. Sister Cecile recovered and her piano launched a 75-year career as a music teacher in schools in Washington D.C., Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Connecticut. She retired in 2000 and moved to Villa Notre Dame in Wilton, Connecticut. Sister Cecile died one day after her 111th birthday, on February 18, 2016.

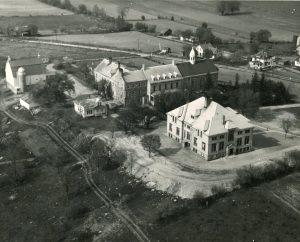

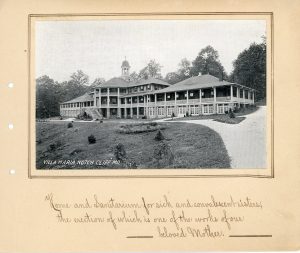

Sister Clara Schutte has an interesting background. She was born in 1882 in Rochester, New York. She attended first grade at Ss. Peter and Paul Parish in Rochester before moving to the Institute of Notre Dame in Baltimore as a boarder where she was welcomed by her two aunts, Sisters Clarissa and Joseph Schutte. She graduated from the commercial program at 16 and returned to Rochester to work as a secretary. After five years of clerical work, she enrolled at St. Mary’s Training School for Nurses, where she graduated in 1907. She entered the School Sisters of Notre Dame two years later. At that time, it was common practice for sisters to work as nurses caring for elderly and ill sisters. Sister Clara is unique, however, because she was the first sister in North America to have a nursing degree. In September 1911, she was sent to Villa Maria in Notch Cliff, Maryland, to assist the existing nurse, Sister Diomede Donahue. Sister Clara spent the next 50 years helping “guide the growth of the Villa, to care for hundreds of her companion Sisters in Christ, serving them until God’s Angel of Death would call—be it at early dawn, bright noon, or quiet eventide.” She died in 1963 at the Villa.

Sisters Dorothy Ann (Charissia) Balser and Victoria Franks (right) standing in front of a car, 1957.

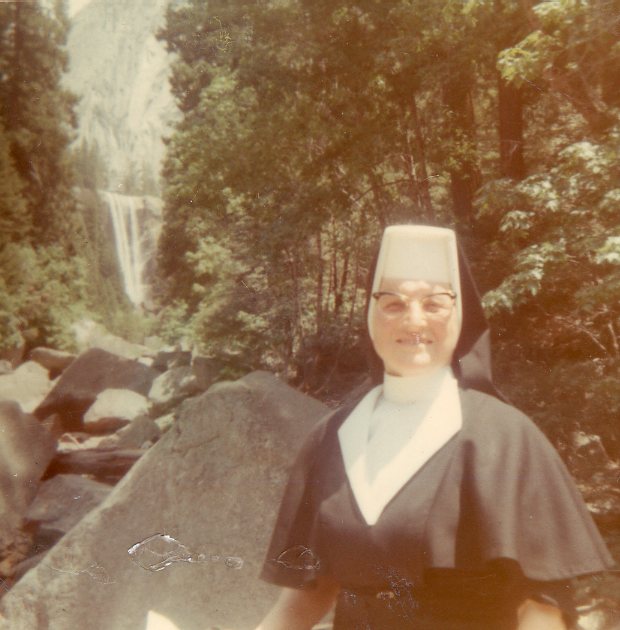

Sister Victoria Franks was born in 1924 in Missouri and entered the congregation in 1943. She spent her first years working as a cook and overseeing the dining rooms in Missouri, Illinois and Mississippi. In 1951, she began working as an elementary school teacher, serving schools in Louisiana and Texas. In 1965, she was appointed as the transportation coordinator at the Dallas Motherhouse in Irving, Texas, making her the “Coordinator of Wheels.” Her duties included providing transportation for the 90 sisters, novices and postulants living at Notre Dame of Dallas in addition to supervising car repairs and making sure tires and gas tanks were full. Her fleet of vehicles included five cars, a 20-passenger junior bus and a 36-passenger bus. In order to drive the larger bus, Sister Victoria had to get a chauffer’s license, making her the first SSND equipped to drive limos and buses! She served in the position until 1973 and afterwards worked in various ministries before retiring in 1994. She died in 1996.

Sister Stanisia Kurkowski (later changed to Kurk) was born in 1878 in Poland and her family immigrated to the United States in 1881. She was a student at the Academy of Our Lady in Chicago before traveling to Munich, Germany, to study under artist Count Tadeusz Zukotynski. She returned to the United States in 1893 and joined the congregation shortly thereafter. She spent her early years working as an art teacher at schools in Wisconsin and Indiana. In 1907, she was sent to her alma mater, Academy of Our Lady, where she established her art studio. In 1919, she earned her bachelor’s degree from the Chicago Art Institute.

Sister Stanisia became well-known for her portraits, murals and religious-themed works. She was commissioned to paint portraits of well-known figures such as then-Monsignor Fulton J. Sheen, Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne, Illinois Gov. Henry Horner, Chicago Mayor Edward J. Kelly, actor Charles Coburn, and archbishop of Chicago, Samuel Cardinal Stritch. She was also commissioned to paint murals and Stations of the Cross for many Catholic churches, including the large central panel for an altar piece in the Basilica of St. Hyacinth and the Stations of the Cross for St. Margaret of Scotland Church, both in Chicago. In 1929, she founded the Art Department at Mount Mary College (now University) in Milwaukee while continuing her commissioned works at her studio at the Academy of Our Lady. Sister Stanisia continued to teach and paint until her death in 1967. In an article written about her work, she was hailed “as the world’s foremost contemporary religious artist.”

For more information about Sister Stanisia, visit https://www.smosparish.com/stations-of-the-cross.html.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, teachers were, in general, not required to have college degrees. Instead, those wishing to teach might attend schools with two-year programs designed to train elementary school teachers. Women entering the School Sisters of Notre Dame were taught how to teach during the two-year candidature.

In the 1920s, states began to set minimum requirements for teachers and many schools were transformed into four-year colleges. Catholic sisters who worked in private Catholic schools were not subject to the same requirements as public school teachers. However, teaching orders of sisters were committed to providing quality education, so they also started sending sisters to college. The problem though, was that the demand for teaching sisters was so high, most congregations could not commit to sending young sisters to a four-year college. Instead, sisters attended college on weekends and over the summer, which meant it could take years to earn a bachelor’s degree.

At the same time, high school education was becoming more common. SSND had been operating institutes and academies for decades, but the number of those schools had always been small. As the number of parish high schools increased, so did the demand for teaching sisters to staff them. Teaching at the high school level required more education than those teaching in elementary schools, so the congregation began sending sisters for not only bachelor’s degrees, but advanced degrees as well. As the educational standards in general were raised, teachers at these schools also needed higher levels of education.

Bachelor’s Degree

Sister Eustochium Kuttner has the distinction of being the first sister to earn a bachelor’s degree as a School Sister of Notre Dame.* She was born in 1862 in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and entered the congregation at the age of 16. During this period, women who entered the candidature had to spend a year taking classes before going out to teach for a year. Sister Eustochium must have shown incredible talent because instead of attending school at the Motherhouse, she was sent to the University of Wisconsin where, in 1880, she earned a Bachelor of Arts in Education. In 1882, she was sent to the Institute of Notre Dame in Baltimore to teach botany and German. She remained there until 1905 when she moved to the College of Notre Dame of Maryland (now Notre Dame of Maryland University). There she taught fine arts, botany and German. She remained at the college until her death in 1936.

* Sister Jeanette Duffy was the first sister identified as having a bachelor’s degree, but she earned the degree before entering the congregation.

Master’s Degree

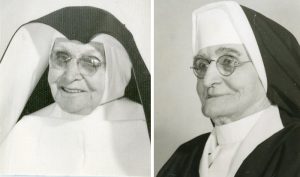

Sister Lioba Diedrich was born in Germany in 1872 and entered the congregation in 1888. In 1890, she was sent to Canada to teach the upper grades of a small two-room schoolhouse in Kitchener, Ontario. In 1907, she became the principal of St. Anne Convent School in Kitchener, the only school that provided high school education for girls in the area. In 1911, she earned a Master of Arts in history from Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario), making her the first SSND to earn a master’s degree. After earning her doctorate from Fordham University (Bronx, New York) in 1925, she became the Directress of Candidates at the Milwaukee Motherhouse and in 1929, she was named the first Dean of Mount Mary College (now University) in Milwaukee. She held that position until 1952. At the age of 80, Sister Lioba volunteered to go to England to teach in Lingfield. In 1957, she retired to the Motherhouse in Waterdown, Ontario, where she lived until her death in 1962. According to her obituary, Sister Lioba Diedrich was “gifted by nature with an exceptionally penetrating mind and a remarkable memory…”

Doctor of Philosophy

Three sisters hold the distinction of being the first to earn a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.): Sisters Immaculata Dillon, Dolores Chavoen and Antonita Emge. All three earned their degrees from Fordham University (Bronx, New York) in 1923.

Sister Immaculata Dillon was born in 1872 in Hagerstown, Maryland. She entered the congregation in 1897 and began her teaching career at Mission High School in Roxbury, Massachusetts. In 1899 she transferred to the College of Notre Dame (CND) in Baltimore where she taught in both the high school and college. In 1917, she was appointed the Dean of Students. In 1921, she transferred to Holy Angels Academy in Fort Lee, New Jersey. For the next three years she took classes at Fordham University while continuing to teach at Holy Angels. In 1923, she earned her Ph.D. Every day she made the long trip from Holy Angels to Manhattan by way of bus, ferry and subway. After completing her degrees in 1923, Sister Immaculata returned to CND to teach until she retired in 1931. She continued to live at the college until her death in 1949.

Sister Dolores Chavoen was born in Philadelphia in 1879. She entered the congregation in 1897 and began her teaching career at the Institute of Notre Dame in Baltimore. She continued teaching in various high schools in Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey and New York, while simultaneously earning a bachelor’s (1916) and master’s (1921) degree from Fordham University. In 1923, she completed her Ph.D. in history from Fordham. After finishing her education, she continued to work as a high school teacher until 1928 when she was named the head of the History Department at Mount Mary College (now University) in Milwaukee. She remained there for six years before returning to high school teaching. In 1937, she went back to Mount Mary and remained there until she retired in 1954. She spent her last years at Villa Maria in Notch Cliff, Maryland. She died in 1964.

Sister Antonita Emge was born in 1885 in Baltimore. She entered the congregation in 1909 and after vows, she was sent to teach at Holy Angels Academy in Fort Lee, New Jersey. While teaching at Holy Angels, she earned her bachelor’s (1921), master’s (1922) and Ph.D. in English (1923) at Fordham University. From 1927-1943, she was the head of the Education Department at the College of Notre Dame in Baltimore before she moved to St. Mary’s High School in Bryantown, Maryland, where she taught science and math. She retired from teaching in 1961 and spent her last years at Villa Maria in Notch Cliff, Maryland. She died in 1983. In an interesting twist, a document was found in her records that provided a summary of her work history. At the end she wrote, “Warning If anyone should write in my obituary that I liked teaching, I will return and haunt them for the rest of their days.”

In 2023, Marquette University in Milwaukee is celebrating “100 Years of the Graduate School.” The University established its Graduate School in the fall of 1922 and since that time, it has awarded nearly 29,000 advanced degrees, including 3,084 doctoral degrees. In 1930, Sister Frances Chantal Oswald finished her dissertation titled, “The training of teachers of Catholic elementary schools with special advertence to the ideals and problems of the School Sisters of Notre Dame,” thus earning her doctorate in education. She was the first woman to be awarded a Ph.D. at Marquette.

Sister Frances Chantal was born in 1884 in Lake Linden, Michigan. She entered the congregation in 1899 and after her profession, she was sent to teach at St. Felix in Wabasha, Minnesota. According to her mission record, she taught grades 9-12 or, as is written, “ALL branches!!!!!” She continued teaching at high schools in Michigan and Wisconsin until 1915 when she was sent to the Milwaukee Motherhouse to act as the co-principal of the candidature high school. While there, she was instrumental in having the school accredited and affiliated with the University of Wisconsin and for establishing a college extension unit at Marquette. As part of this extension program, she earned a bachelor’s (1918) and a master’s degree (1922) from Marquette before entering the Ph.D. program.

In 1933, Sister Frances Chantal was transferred to Mount Mary College (now University) in Milwaukee to serve as registrar. After nine years, she returned to teaching at high schools in Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois before retiring in 1950. She died in 1955.

Sister Theophila Bauer (top left) pictured with other early SSND Pioneers:

(back row, l-r) Sister Theophila Bauer and Sister Seraphica Mitchell; (front row, l-r) Sister Seraphina von Pronath, Mother Caroline Friess and Sister Emmanuela Schmid

Mother Theophila Bauer was born in Bavaria in 1829 and entered the congregation in 1845. In 1848, she joined the second band of missionary sisters who traveled from the Munich Motherhouse to the United States. She spent her first years teaching at parish schools in Baltimore. In 1856, she was called to Milwaukee to serve as the school supervisor, candidate’s mistress and Mother Caroline Friess’ assistant. In 1877, Mother Theophila was appointed provincial of the Baltimore Province, a position she held until 1888. After her third term ended, she was appointed to serve as the convent superior for the Notre Dame of Maryland Preparatory School and Collegiate Institute for Young Ladies in Govanstown, Maryland.

In 1895, Mother Theophila and Sister Meletia Foley (director of the Collegiate Institute) received permission to move forward in establishing a four-year Catholic women’s college. The congregation applied to the Maryland General Assembly for a college charter and in 1896, the original school charter was amended to grant power to award bachelor’s degrees in arts and science, literature and music. In September 1895, students in the Collegiate Institute’s senior department were enrolled in freshman-level classes and over the next three years, the college added sophomore, junior and senior classes. In 1899, the College of Notre Dame of Maryland (now Notre Dame of Maryland University) awarded four Bachelor of Arts degrees and two Bachelor of Literature degrees to six young women, the first women to earn a bachelor’s degree from a Catholic college in the United States. The College of Notre Dame was the first Catholic woman’s college in the United States and Mother Theophila was its first president. She served as the college’s president until her death in 1904.

Sister Charitas Krieter was born in 1892 in Turkey Creek, Indiana. She entered the congregation in 1909. She worked at high schools in Michigan, Indiana and Wisconsin until 1931 when she was called to teach education at Mount Mary College (now University) in Milwaukee. In 1952, she returned to teaching in high schools and at the age of 70, she left to teach at the University of Javeriana in Bogotá, Colombia. A year later she returned to finish out her career as an English teacher at West Catholic High School in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In addition to years of teaching, she authored 15 books. However, it is neither her teaching or authorship that make her unique—it was her sideline career as a handwriting analyst.

In 1933, Mount Mary held a carnival to raise money to support the student literary magazine. There was a notice in the sister’s dining room asking for “anybody who knows how to make money without too much overhead.” Sister Charitas requested a booth that completely concealed her, except for a small opening in the front. For a quarter, a person could slip her a handwriting sample, which she would analyze. She claimed that based on a person’s handwriting she could accurately describe their personality—was the writer quick to temper, artistic, easy going or humorless? The booth was a huge success and it launched Sister Charitas into the national spotlight.

Several years later, her talent was featured in a national magazine and as a result, she received letters from all over the world asking her to analyze handwriting. She charged $5 for each analysis, with the proceeds going back to the SSND community. She estimated that she analyzed 1,000 handwriting samples each year. The highlight of her sideline career was an appearance on the gameshow, “What’s My Line.” The show, which was taped on November 5, 1970, featured guests Soupy Sales, Phyllis Newman, Bennett Cerf and Arlene Francis asking questions trying to guess Sister Charitas’ profession. (Phyllis Newman correctly guessed sister’s profession.)

Sister Charitas retired in 1980 and spent her remaining years in Elm Grove, Wisconsin. She died in 1992.

Watch Sister Charitas’ episode of "What’s My Line" on Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQJ7d0bY33A.

To hear Sister Charitas talk about her life, visit https://www.sturdyroots.org/sisters-stories/tell-us-a-story