In 1990, 678 School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) from what are now the Atlantic-Midwest and Central Pacific Provinces volunteered to participate in a study on aging, Alzheimer’s, and related dementias. To take part in the study, the sisters agreed to periodic cognitive and physical assessments throughout the rest of their lives as well as brain donation at death. The endeavor was a new undertaking, but it fit seamlessly with the sisters’ commitment to being educators in all they are and do.

Nun Study scientists welcome sisters to the brain bank where the priceless specimens donated by sisters are kept.

Although all the sisters enrolled in that investigation, dubbed the Nun Study, are now deceased, the contributions of those women continue. At this year’s SSND Women’s Leadership Luncheons, Dr. Margaret Flanagan and Dr. Sudha Seshadri, two scientists still conducting research using the material provided by the sisters, explained what has made the Nun Study so unique and how it continues to shed light on Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“The Nun Study was specifically one of the first studies of its kind to require that individuals not have memory problems at the time of enrollment,” said Dr. Flanagan, who directs the Nun Study, now housed at the UT Health San Antonio’s Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases. “It really introduced the concept of studying earlier disease onset to try to determine some of the earliest changes that happen in the brain.”

One enormous benefit of using a group of religious sisters as study subjects was the uniformity in their lifestyles. The similarity of sisters’ housing, nutrition, health care, income, and social networks removed many confounding variables, making it easier for researchers to determine what factors increase or decrease the risk of dementia. In addition, the detailed record-keeping maintained by the congregation provided scientists with a wealth of information from sisters’ early life, including family history and early writing samples. The sisters also had an unusually high brain donation rate, providing the opportunity to compare neuropathology findings from both impaired and healthy brains, which had been historically difficult.

Significant findings from the Nun Study include new knowledge about:

-

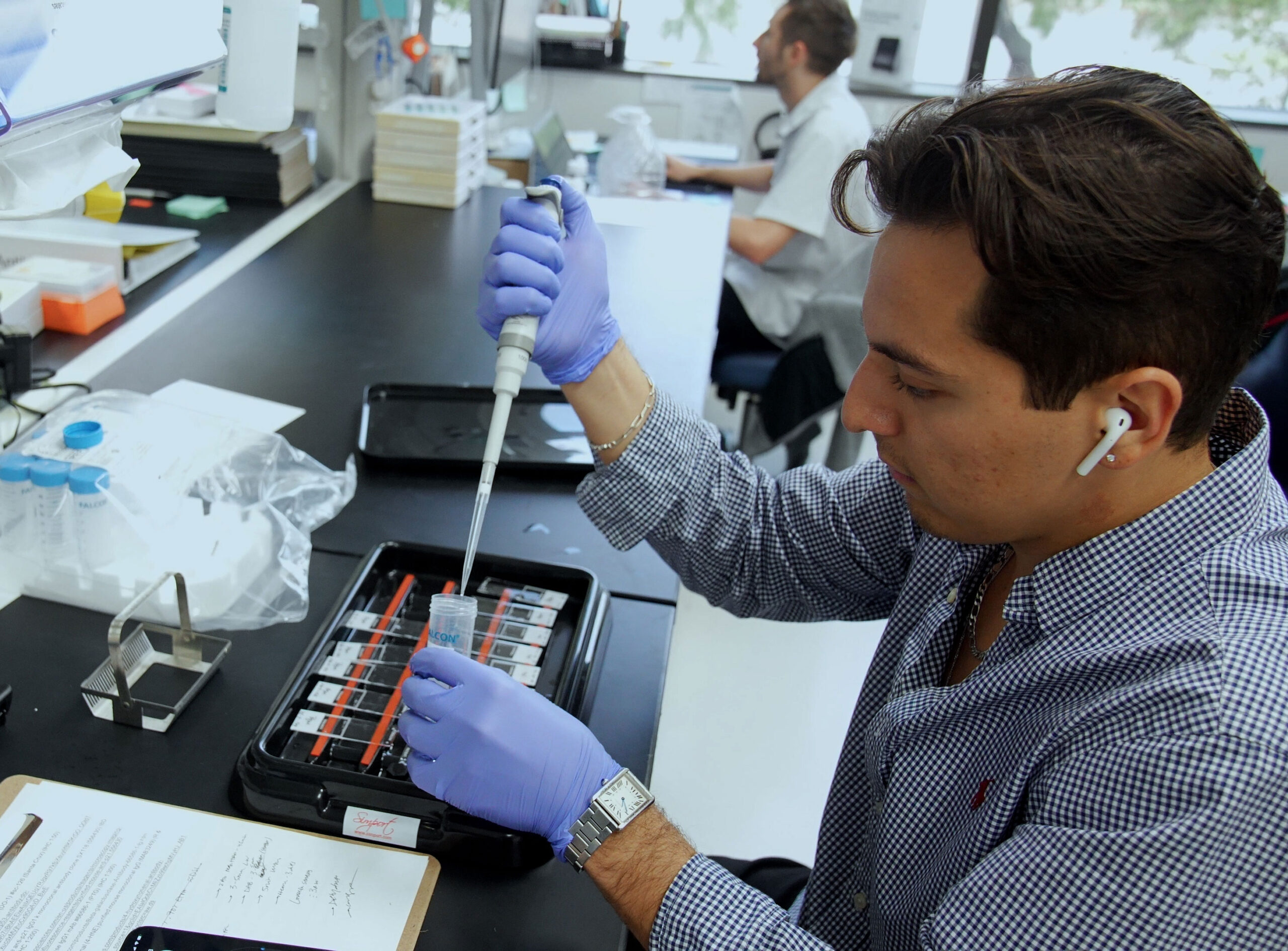

Scientists with the Nun Study continue to push the boundaries of Alzheimer’s research.

Cognitive resilience and neuropathology: Some study participants exhibited significant pathological changes within the brain without exhibiting symptoms of cognitive decline, indicating the existence of factors that contribute to cognitive resilience despite the presence of Alzheimer’s pathology.

- Genotypes and dementia risk: Researchers identified a specific risk gene that increases the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease as well as a protective gene that may reduce the risk.

- Early-life predictors of cognitive health: The relationship between early-life linguistic ability and later-life cognitive function is a major finding of the Nun Study. Scientists have found that high idea density and grammatical complexity in young adulthood correlates with a lower risk of cognitive impairment in later life.

- Comorbid neuropathologies and dementia risk: The Nun Study emphasizes that most cases of dementia involve the coexistence of several different pathologies. The presence of these multiple brain pathologies suggests that multi-targeted therapeutic strategies may be necessary.

In addition to using data to conduct their own research, the staff of the Nun Study is working to digitize all study materials to make information available to other researchers. With digital pathology and artificial intelligence reshaping the study of Alzheimer’s and related dementias, there is great hope for further advancement in precision diagnosis and preventive intervention of cognitive decline.

“I expect that over the next four or five decades we will continue to learn secrets by studying this treasure trove,” said Dr. Seshadri, founding director at the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s & Neurodegenerative Diseases. “We are just beginning to mine the information.”